Artist Interviews 2021

Desert X

By Julia Annabel Siedenburg & Laura Siebold

Desert X 2021 – A Journey Into The Desert

Desert X seeks to engage the viewers by presenting art in open spaces, accessible and free to anybody who passes by.

Those who are interested in contemporary art get a chance to experience diverse culturally and historically inspired pieces from selected artists around the world.

The first Desert X exhibit opened to the public in 2017, showing artworks from 16 artists in different locations in Coachella Valley and Palm Springs.

After a secondary edition following in 2019, the Desert Biennial Organization extended the project, creating a presence outside the U.S. in 2020.

In 2021, Desert X returned to its original location in Coachella Valley between March 12, 2021, and May 16, 2021.

Curated by Neville Wakefield and Co-Curator César García-Alvarez with 13 participating artists from eight countries exhibiting their work in the context of Desert X 2021,

the organization seeks to make art accessible and (re-)open a dialogue about the desert as a natural form and the product of human narratives:

The exhibition explores the desert as both a place and idea, acknowledging the histories, realities and possibilities of people

those who reside in the Coachella Valley and the political, social, and cultural contexts that shape their stories. Imagining

the landscape as both an amalgamation of natural forms and a terrain forged by people, the 2021 edition refuses the notion of

the desert as homogenous entity. Newly-commissioned works address themes of land rights and ownership, the desert as border,

migration, water exploitation, social justice, racial narratives of the west, the gendered landscape and the role of women

and young people and the creation of new dialogues between regional and global desert experiences. (Official Desert X Opening Release)

The Desert X 2021 edition seeks to explore the idea of the desert as a journey and tells a narrative of how this journey has been and continues to be shaped by minorities.

The exhibit includes diverse communities in the Coachella Valley and around the world and looks at how these communities are shaped by the past, present, and future of

the desert as a landscape and an idea, recalling memories and diverse narratives. For those who did not make it this year, we have created a virtual

experience of our Desert X 2021 journey.

Our journey started with a 2.5-hour drive from Los Angeles with our first stop being the Ace Hotel & Swim Club where we learned that

– yes, you can pick up a physical Desert X map there, but only on Thursdays, Fridays, and on weekends. As you can guess, we stepped into the lobby of the

hotel on a weekday (Wednesday) to avoid expected crowds. That was the point at which we discovered the brilliant features of the virtual Desert X map.

Not only does the app present information about the exhibits of the 13 distributing artists, but it also offers a direct connection to popular map apps

like Google Maps to help visitors locate the locations of the outdoor exhibits.

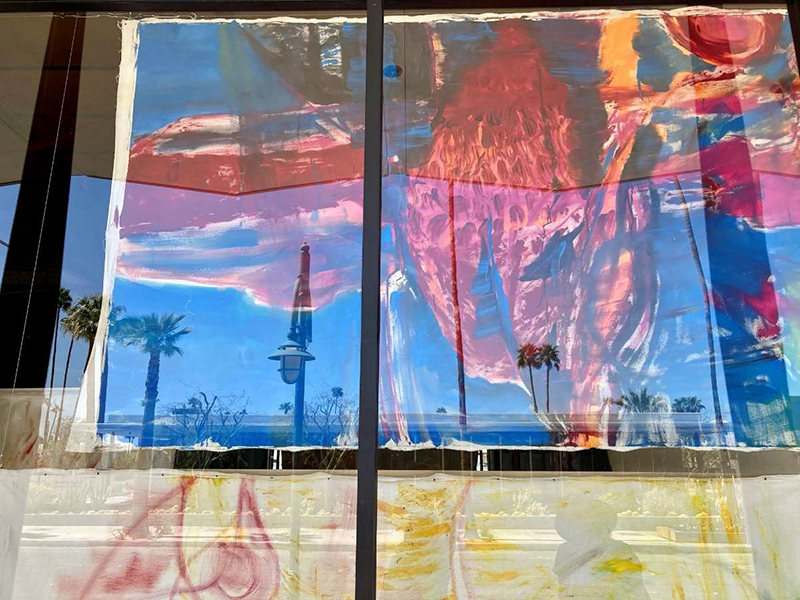

Starting off our art journey in the City of Palm Springs, we visited Vivian Suter’s Tamanrasset first. Suter’s art pieces stretch around an entire

modernist building in Downtown Palm Springs and can only be observed from behind glass. The large paintings, some of which reach from floor to ceiling,

show organic and natural shapes inspired by the Suter’s emotional response to the desert landscape. As Covid-19 travel restrictions limited her ability

to experience the desert landscape in person, the artist’s feelings and emotions were mainly based on pictures of the region and desert landscape.

Suter’s strong visual interpretations of a landscape seen only from distance support this year’s Desert X theme – that the desert is not only a place,

but also an idea that can be experienced emotionally, culturally, and historically. Interested in the dimension of the desert as an imaginary force,

Suter creates a physical and psychological dimension through landscape paintings.

We found the positioning of the paintings in Downtown Palm Springs was an efficient move in merging the natural and the communal space. The reflections

in the glass of the surrounding landscape and ourselves which we caught while taking photographs reinforced the message of the exhibit – creating a

dialogue between art, the desert landscape, and the visitor. We had a chance to see the artwork again; a bright gallery of organic forms inviting the

viewer to come closer.

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold / Julia Siedenburg

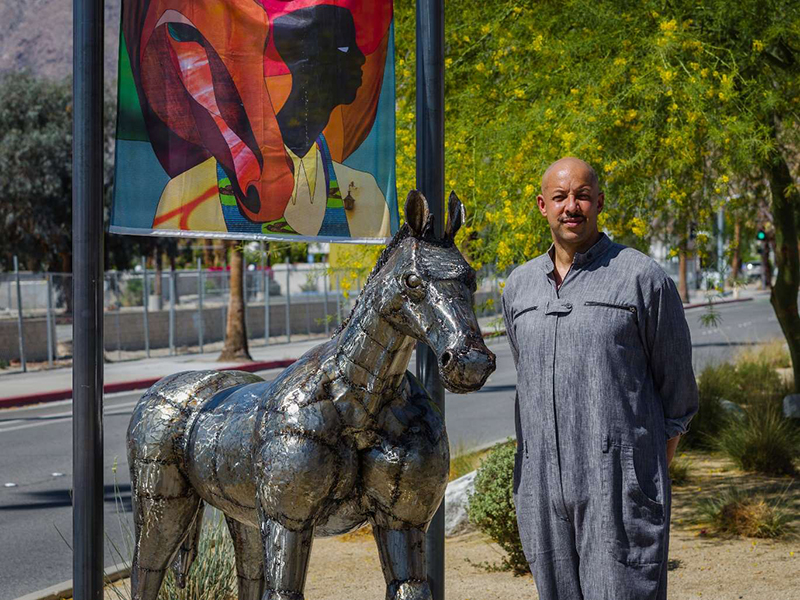

After Vivian Suter’s Tamanrasset, we tried to locate Christopher Myers’ The Art Of Taming Horses, supposed to be located on Tahquitz Canyon

Way between Sunrise and Civic Drive. Driving up and down Tahquitz Canyon Way several times, we figured that either this particular exhibit had not

opened yet, or that someone had stolen some statues and the artwork had been removed for safety. Our first guess proved to be right. With the statues

of horses being draped in banners since the unveiling of the artwork on April 9, Christopher Myers seeks to tell the fictional story of one Mexican

and one African-American rancher who created a common narrative by initiating a community – nowadays Palm Springs – to pursue their love for raising horses.

By reshaping the meaning of the Equestrian statue, the artists address the gap between history and mythology. He seeks to draw attention to undocumented

storytellers that have traveled south, crossing the desert, in search of freedom and establishes the idea of home for desert communities.

Photo Credit: Lance Gerber

Photo Credit: Lance Gerber

Statue and Christopher Myers’ son. Photo Credit: Colin Robertson.

Our next visit led us to Nicholas Galanin’s powerful 45-foot Indian Land™ sign, located at the base of Mount San Jacinto across the visitor center to

Palm Spring’s Aerial Tramway. While the title has been trademarked and used in previous works by the artist, it appeared extremely powerful to us, set

against the background of the desert landscape. By naming his work Never Forget, Galanin acknowledges indigenous communities as the rightful owners

of the desert land and calls for corrective action:

Never Forget asks settler landowners to participate in the work by transferring land titles

and management to local Indigenous communities. The work is a call to action and a reminder that land acknowledgments become only performative when

they do not explicitly support the land back movement. Not only does the work transmit a shockwave of historical correction, but also promises to

do so globally through social media. (Nicholas Galanin, Never Forget, desertx.org)

With a strong association to the original HOLLYWOODLAND sign in Los Angeles County, Galanin not only evokes the idea of white narrative in film but also

challenges the traditional white settler mythology of the West, starting a conversation that couldn’t be more contemporary and valid than right now.

The removal of indigenous communities from their land equals a removal from life itself; Galanin’s work is directed towards a broader understanding of

these forgotten histories.

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Located across the highway from Galanin’s Indian Land™ letters, we made our way to Serge Attukwei Clottey’s The Wishing Well.

The Wishing Well is a testimony to the importance of water across the world.

The official description of the Desert X exhibit reads as follows:

The Wishing Well is a sculptural installation of large-scale cubes draped with sheets of woven pieces of yellow plastic Kufuor

gallons used to transport water in Ghana. Transforming a public park into a destination, The Wishing Well refers to the wells to

which many people around the world must trek daily to access water. Europeans introduced Kufuor gallons, or jerrycans,

to the people of Ghana to transport cooking oil. As repurposed relics of the colonial project, they serve as a constant reminder of the

legacies of empire and of global movements for environmental justice. Sited in the Coachella Valley, whose future is deeply dependent

on water, The Wishing Well creates a dialogue about our shared tomorrow. (Serge Attukwei Clottey, The Wishing Well, desertx.org)

The choice of location for this sculptural installation is linked to the choice of the Coachella Valley whose existence as a thriving landscape

depends on water. The artwork was created to engage the community as part of the artistic process. Yellow representing The World and the idea of

Richness, Serge Attukwei Clottey opens a conversation across geographies, communities, and cultures by addressing a universal problem:

Access to clean water. To us, yellow reflected the color of the sun, illuminating the art piece against the backdrop of a blue sky.

It acknowledges the importance of a resource that gives communities across the world access to life, and whose accessibility too often receives too little value in contemporary times.

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold / Julia Siedenburg

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

Once we had enough of the Wishing Well, we continued our journey. This time, the drive was a little further. We drove to Rancho Mirage,

across Frank Sinatra Boulevard, and down Bop Hope Drive and found ourselves at a beautiful big white bungalow-style event space called

Sunnylands Center & Gardens. Sunnylands was the wedding venue for Frank Sinatra and through the years has already housed a lot of big

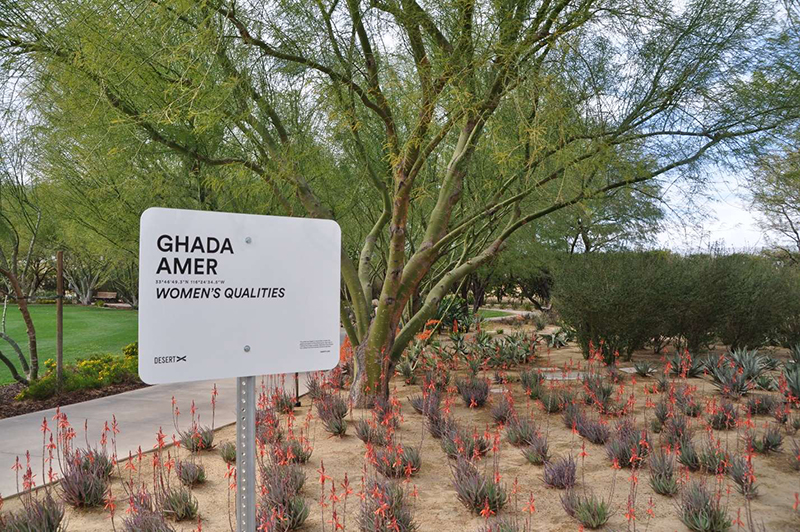

celebrities, political figures, and even the royals themselves. Sunnylands is the location where Ghada Amer installed her work titled

Women’s Qualities for the 2021 Desert X exhibition. Her art piece is a continuation of her Women’s Qualities series: By taking art out of traditionally

feminine spaces and into the household, Amer creates a space for the self-fulfillment of women through art and gives them the right to shape art

history and painting through aesthetics and content:

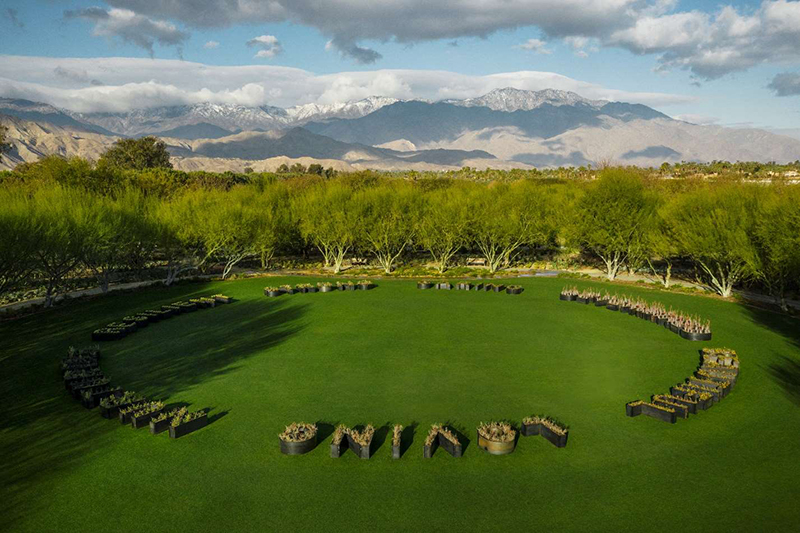

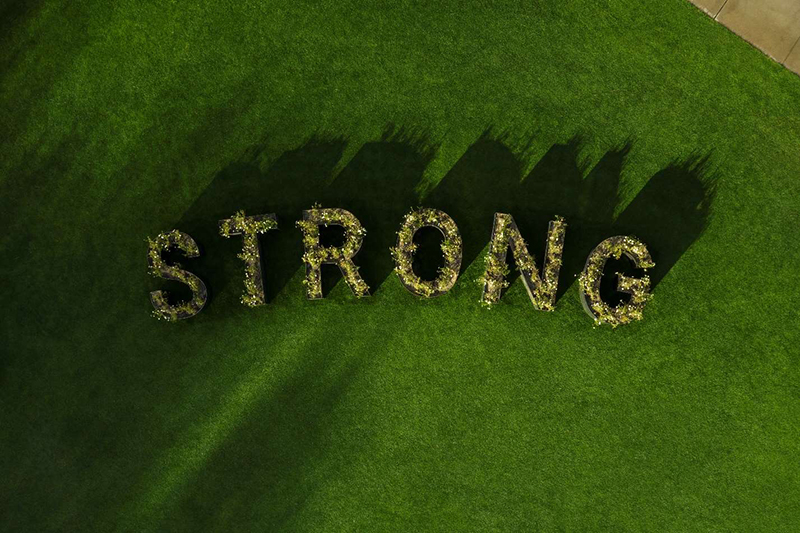

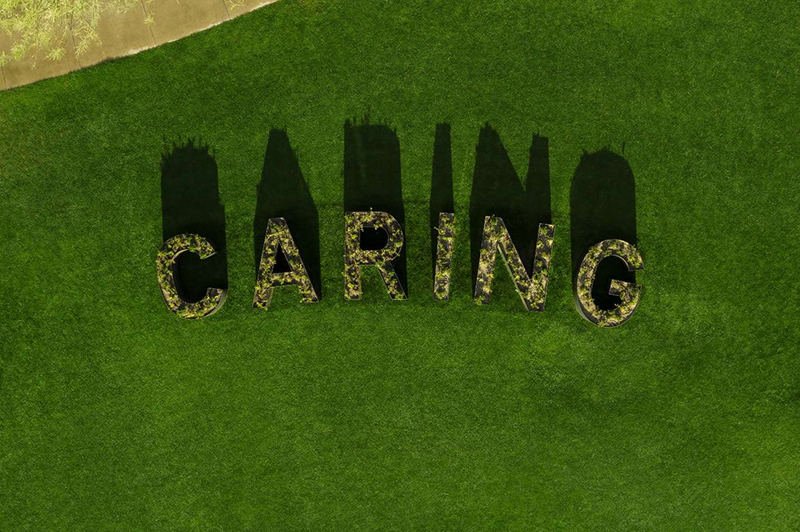

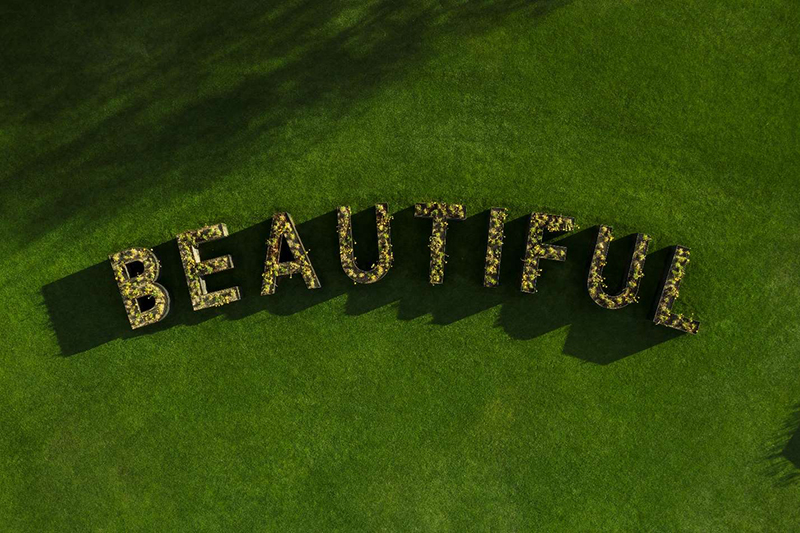

For Desert X, Amer continues her Women’s Qualities series, asking men and women in the Coachella Valley to share words that describe

the qualities with which they identify and to which they have been ascribed. It is an act of looking both inward and outward, yielding

a form of self-portraiture. The result is a grouping of words arranged on the circular Great Lawn at Sunnylands.

The installation forms a meeting place where artist and community, aesthetics and ideology, nature and culture come together for reflection and contemplation. (Ghada Amer, Women’s Qualities, desertx.org)

Ghada is a big advocate for women’s rights and equality and with this exhibit she wanted to showcase just that. She wanted to speak to women

directly and so formed kind words out of letter planters. There are 7 words total that together form a circle in the middle of the Great Lawn.

The work marks Ghadas’ first outdoor exhibit which had a very strong, female character. Being placed in Sunnylands Center & Gardens,

Amer employs a historical space, a space used for leisure by prominent figures and politicians in the past, to change the future for

women in the arts. While we would have enjoyed an aerial view of the exhibit, the positioning of planted qualities as words carried a

sense of hope and change that was reinforced each time you walked by to look at the planted art.

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit for all aerial images and artist image: Lance Gerber

Our last stop for the day is the furthest exhibit piece in the Desert X program. Located next to the Palm Desert Chamber of Commerce

by Joshua Tree stands Kim Stringfellow’s Jackrabbit Homestead tiny house. It is a cute mint green-colored house made of wood with a

flat white roof, brown wooden door, and small windows on all four sides. As we peeked through one of the windows, we saw that the

Homestead house almost had everything inside one would need. It was packed with a stove, oven, and a typing machine sitting there

waiting to be used. Just a bathroom was missing. Kim Stringfellow based this exhibit piece on her book Jackrabbit Homestead:

Tracing the Small Tract Act in the Southern Californian Landscape 1938-2008.

The 112-square-foot cabin she created for Desert X trades the stark, solitary romanticism of sand and sky for a small patch of sprawl

nestled between the Palm Desert Chamber of Commerce and a CVS Pharmacy. Decontextualized in this way, the diminutive and unglamorous

1950s proletariat kit home becomes a beacon for conversations about class, sustainability, capitalism, public land, and the commons. (Kim Stringfellow, Jackrabbit Homestead, desertx.org)

While walking around the cabin to look into every window from every angle, we started to hear a woman’s voice coming from inside the cabin.

Her story is intercut with sounds and music. We later learned that it is an audio collaboration piece designed for the exhibition by Georgia-based musician/artist/author

Jim White and fellow Georgian singer/songwriter Claire Campbell. Tim Halbur contributed to sound design. The Woman’s voice was that of Catherine Venn Peterson,

who once shared her homesteading experience in the 1950s with Desert Magazine. The voice is so calming; you could stay and listen to it forever.

And the longer we looked at the house, the more we started to wonder how the desert life would be like and how much you need to survive to be truly happy.

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

On the second day of our desert journey, we drove by Xaviera Simmons’ Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A Militia, a series of billboards

positioned on Gene Autry Trail. The billboards were crafted to propose an alternate narrative, one that seeks to create a monument for marginalized

groups of a non-white America:

It is not that Indigenous or First Nations people or the Black descendants of American chattel slavery have never had the imagination for monuments,” Xaviera Simmons says.

“It’s that white America, particularly as represented and enforced by local, state, and federal governments, has consistently attempted and often succeeded to terrorize

the impulse of self-defining monumentality out of those groups — groups which my own ancestry rests. (Xaviera Simmons, Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A Militia, desertx.org)

While we absolutely value the mission of giving the unheard voice a voice through visual representation, we wished that the billboards had been positioned elsewhere than along the

highway to allow deeper engagement. We drove back and forth Gene Autry Trail several times to catch a glimpse of the billboards, but still felt the insufficient grasp of Simmons’ art piece.

Ultimately, the messages on the billboards, like the stories of underrepresented citizens of Black America, deserve deeper reflection than can be accomplished by simply passing by.

Maybe this is the challenge we need to commit to – becoming deeply engaged instead of simply just passing by.

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

For the following installation, we had to reserve a time slot to visit beforehand. Again, we drove a little further away from Palm Springs into Sky Valley.

Around us were mainly desert, mountains, and trailer communities, and a palm farm once in a while.

We did not know that, once we arrived there, we had to walk up a steep winding road. Alicja Kwade is originally from Poland and is currently based in

Berlin. Her ParaPivot (sempiternal clouds) was located on top of the hill. The installation was built out of oversized black interlocked metal frames

and big white pieces of marble blocks between them. As you walk around it, you realize that it looks different from every angle, and it seems as if it could all fall apart at any moment.

The array of steel and stone draws viewers into the frame of this massive yet fragile universe where simple forms yield complex meanings. As you approach and move in and out of its frames,

you become aware of the experiential equivalent of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, an effect whereby observer interaction changes the form of the thing being interacted with.

The result is an illusion of instability. (Alicja Kwade, ParaPivot (sempiternal clouds), desertx.org)

The white marble stone pieces shined and shimmered in the sunlight. I think this was one of my favorite pieces of the entire exhibit, even with the hike that we had to do to get it.

The view was beautiful from up top. ParaPivot is supposed to showcase the idea of time and space and how it can very well apply to being in the desert -the feeling of losing time

and unidentifiable space around you.

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

Our last stop on our Desert X exhibit journey was located in an empty desert field in Desert Hot Springs. As we parked our car on the side and eventually spotted the piece, we thought to ourselves –

Desert X really makes you work for it. But it has been worth it every time. After a walk over uneven terrain, we finally arrived at the enormous wall made out of what at first

looked like fabric pieces that were stacked on top of each other. Standing right in front of the wall was impressive. It seemed so steady and so unstable at the same time.

Zahrah Alghamdi, a Saudi Arabian artist, is the person behind this exhibit called What Lies Behind The Walls. She is known for using great mixtures of materials to create

incredible pieces like the desert installation that portray the history and culture of different places building on top of each other. She got inspired right away when she first saw the

Palm Springs desert landscape.

For Desert X, she has created a sculpture that echoes and synthesizes the traditionally built forms from her country with the architectural organization

she found in the Coachella Valley. The result takes the form of a monolithic wall comprised of stacked papers impregnated with cements, soils, and dyes specific to each region.

(Zahrah Alghamdi, What Lies Behind The Walls, desertx.org)

For Zahrah, the idea and effect of memory are always in the back of her head when she creates her installations. As you touch one of the layers, you feel the leather, clay, and

rocks combined to make the layers that form the wall. It all comes back to the elements that the world has to offer.

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

Photo Credit: Laura Siebold

Photo Credit: Julia Siedenburg

Desert X 2021 -Participating artists

Zahrah Alghamdi (born 1977, Al Bahah, Saudi Arabia, based in Jeddah)

Ghada Amer (born 1963, Cairo, Egypt, based in New York)

Felipe Baeza (born 1987, Guanajuato, Mexico, based in New York)

Judy Chicago (born 1939, Chicago, US. based in Belen, New Mexico)

Serge Attukwei Clottey (born 1985, Accra, Ghana, based in Accra)

Nicholas Galanin (born 1979, Sitka, Alaska, US, based in Sitka)

Alicja Kwade (born 1979, Katowice, Poland, based in Berlin)

Oscar Murillo (born 1986, Valle del Cauca, Colombia, based in various locations)

Christopher Myers (born 1974, New York, US, based in New York)

Eduardo Sarabia (born 1976, Los Angeles, US, based in Guadalajara, Mexico)

Xaviera Simmons (born 1974, New York, US based in New York)

Kim Stringfellow (born 1963, San Mateo, CA, US, based in Joshua Tree)

Vivian Suter (born 1949, Buenos Aires, Argentina, based in Panajachel, Guatemala).

Additional resources consulted in the making of this article:

https://desertx.org/dx/about

DX21 – Official Exhibit App

Nicholas Galanin/Indian Land: https://www.desertsun.com/story/life/entertainment/arts/2021/03/08/desert-x-indian.land-piece-palm-springs-already-drawing-buzz/4630215001/ (Accessed April 13, 2021)

|

|