Op-Ed 2025

The Scars We Cannot Erase

By Johnny Otto

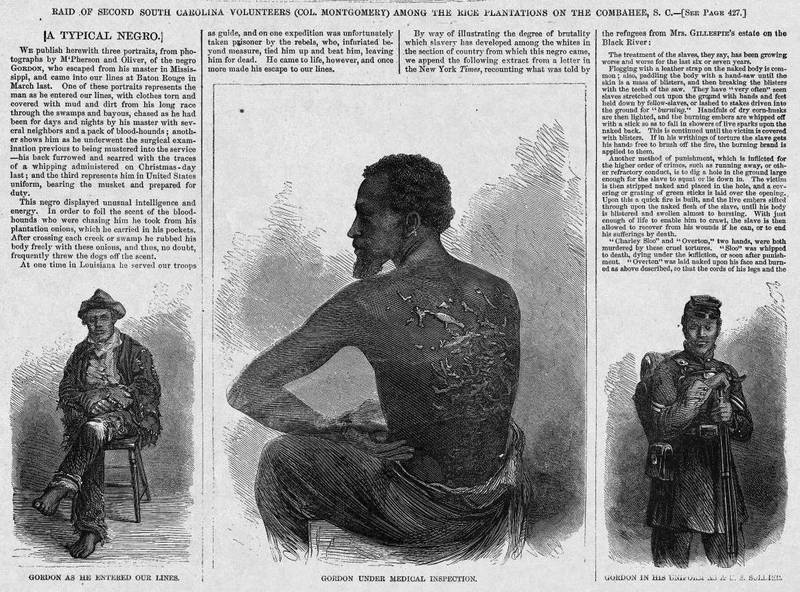

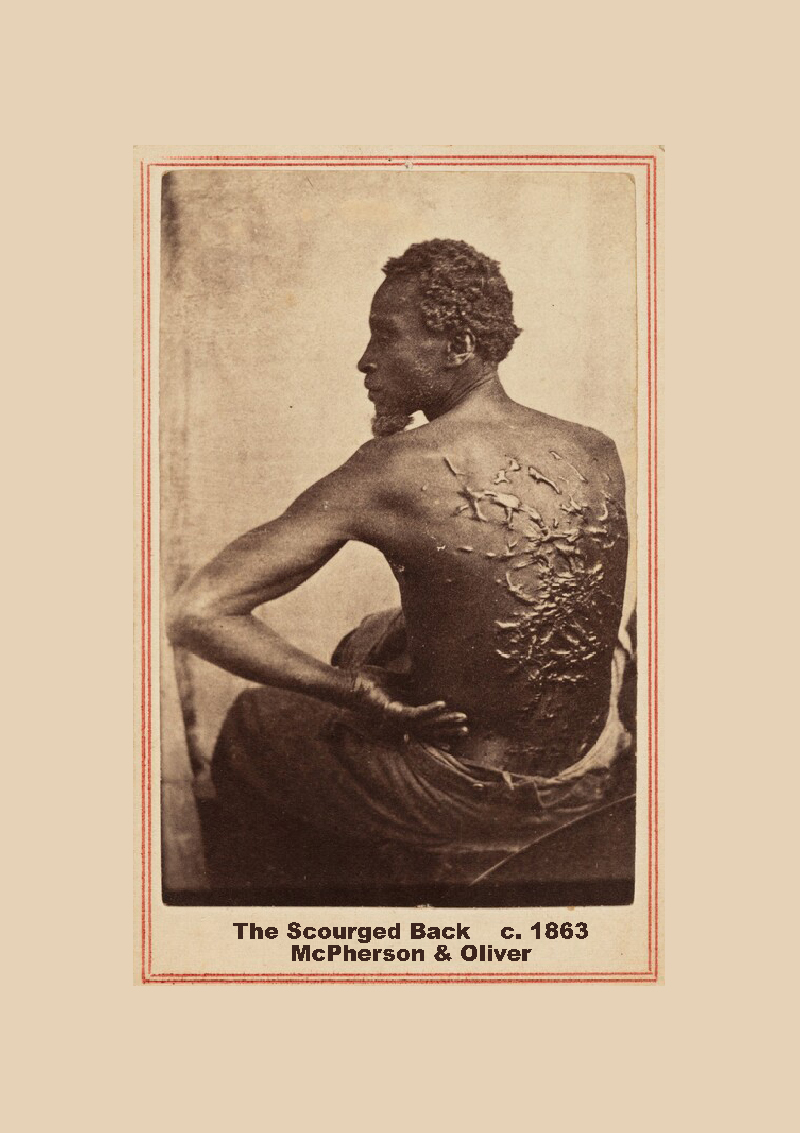

In 1863 a man named Gordon fled enslavement in Louisiana and reached Union lines. In a Union field hospital he sat for the photographers McPherson and Oliver. He turned his back to the camera. The photograph, now known as The Scourged Back, reveals a body covered in thick ridges of scar tissue from years of brutal whipping. The image is not simply a portrait of one man. It is a record of what slavery was in practice. It is history branded onto human skin.

The photograph quickly spread across the North. It appeared as a small albumen print, a carte de visite that could be purchased, carried, and shown from hand to hand. On July 4 of that same year Harper’s Weekly published it as an engraving alongside two companion images: Gordon as he entered Union lines and Gordon wearing the uniform of a Union soldier. Together the images told a story of bondage, survival, and transformation. For many Americans who had only read accounts of slavery, these photographs were the first undeniable visual evidence of its violence.

Frederick Douglass had already provided the words for this truth. In 1852, in his speech What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?, he asked his audience: “What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash … to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh … Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood … is wrong? No! I will not.”

Douglass’s refusal to argue was deliberate. He would not pretend that the morality of slavery was a matter of opinion. To him the evidence was so overwhelming that debate was an insult to reason and to humanity. His words forced listeners to confront a truth they already knew but wished to avoid. The photograph of Gordon made the same demand. Where Douglass offered oratory, Gordon offered scars. Both stripped away the possibility of denial.

Today reports suggest that the Trump administration has directed federal agencies to remove or cover images such as The Scourged Back from certain public sites. The stated rationale is that they are negative or corrosive to national pride. In reality they are uncomfortable. They make visitors see what slavery actually was.

The danger of this reasoning has a precedent. The Nazi regime in Germany removed and destroyed images and artworks that it believed undermined national pride. Modernist paintings were mocked as “degenerate.” Photographs that showed diversity, dissent, or weakness were censored or altered. Book burnings purged entire traditions of thought. In their place the regime promoted only heroic depictions of Aryan bodies, rural virtue, and militarized strength. By removing images that told the truth of a more complex and painful reality, they replaced history with propaganda.

The United States should never follow that path. The purpose of public history is not comfort. It is truth. The scars on Gordon’s back are not only his own. They are the scars of a nation built on forced labor. To erase them from view is to erase the testimony of millions. It is to teach future generations that America can be celebrated without being examined.

There is a responsibility in displaying images of suffering. When shown carelessly they risk turning into spectacle. Yet this photograph restores dignity rather than stripping it away. Gordon chose to present his wounds during a medical examination that documented the price of slavery. Other images in the sequence show him arriving at Union lines and later standing as a soldier in uniform. His body carried scars, but his life carried forward. The arc is not humiliation. It is transformation.

Removing this image from the public sphere does more than suppress a document. It suppresses a witness. It tells the descendants of the enslaved that their ancestors’ pain can be hidden when it feels inconvenient. It tells citizens that patriotism requires blindness. It prepares a generation to inherit pride without memory, which is no pride at all.

The lesson of Douglass’s speech and Gordon’s photograph is the same. Slavery does not require argument to prove its evil. The proof exists in scars and in testimonies, in bodies and in words. A country willing to see those proofs has a chance at honesty. A country that hides them chooses denial.

The Scourged Back is not an attack on the United States. It is a reminder of what the United States had to overcome. To display it is not to shame the nation. It is to honor the endurance of those who suffered and still demanded freedom. It is to acknowledge that a democracy cannot live on praise alone. It must live on proof.

Remove this photograph and we turn away from both Gordon and Douglass. Keep it visible and we may learn how to face the scars of our history and still move forward.

|

|