Artist Interviews 2021

Kevin Komadina

By Laura Siebold

Kevin H. Komadina is an oil painter, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. A former doctor and ceramic artist, Kevin invites his viewers to become part of his image and adding to it, by finding “their ‘story’ in the painting”, as Kevin puts it. In Kevin’s paintings, past, present, and future collide, highlighting both the transience, as well the opportunities of human life.

Kevin’s choice of images often points towards the simple pleasures of life – people eating food at a diner, or enjoying a ride on a ferris wheel. The most distinct feeling you get from experiencing Kevin’s images is a representation of the many facets of the human experience.

In his interview, Kevin talks about his path from ceramics and pottery to oil paintings, revealing stories from his personal life, travels to Guatemala, and the ways he draws from the environment and art before creating a painting. Kevin’s work is proof that the imperfections of life can be a positive force in creating change and channeling creativity.

“At the Museum”, 2020

You create astonishingly realistic images of different scenes of life with oil. How do you choose your subjects and what is the message you want to send with your art?

I want to thank you for taking an interest in my work, and for the opportunity to share my thoughts about painting and life. I am grateful to be a part of Art Squat. Also thank you for that compliment. For the longest time I have wanted to paint “loose”, I have come to accept that I may be constitutionally incapable of painting in that manner.

My subjects come to me both intentionally and organically. I try to be mindful as I am going through the day of the images around me, and when see a scene that strikes me, I take a quick photo and it becomes the start of a painting.

For example, I was volunteering at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and saw a woman walking down the hall with her small son. The geometry of the architecture, the light and shadow, the marble floor, and the image of the woman with her son struck a chord with me. I snapped a quick iPhone photo, and that was the beginning of “At the Museum”. I returned on several occasions to observe the lighting at that time of day, as photos do not capture all that is necessary. “At the Museum” is about our humanity and the arc of life. We have all been the child, many of us have also been the parent. As a child we have been taken on outings, some successful others not; as parents we have had joys and struggles with our children. The other important point is the link of past and present, mother and child and art from all ages.

A local theater had a beautiful neon marquee, and it was a reminder of a different era; there was a richness to it not present in many of our modern multiplexes, and “Mainstreet USA” became a painting. That image made me seek out similar structures in the Minneapolis area, in that way I discovered the H-Lo dinner, a Fodero diner created in 1957. The stainless steel exterior contrasted with the soft and colorful interior lighting and the clientele, the industrial and the human merged into a beautiful harmony resulting in “Evening Shift”. The diner is a popular gathering place for many 20’s and 30’s again highlighting a connection of past and present.

The “O’Keeffe” series of paintings is an example of organic inspiration. My wife and I were visiting the home of Georgia O’Keeffe in 2018. I have always admired her work. Her spirit filled the space, and her sources of inspiration were all around in the landscape. I loved the texture of the adobe, and the plants, the color of the sky and the clouds so close that one can almost touch them. I felt a powerful connection to the space and felt compelled to paint it. This series was painted from slightly altered angles and perspectives, the aim being to give one pause and to think about the image in a different manner.

In summary, the message I want to send is to highlight our shared humanity by having the viewer connect with the image in the painting and to find their “story” in the painting. I have had people contact me about “The Breakfast Club” asking where the image was from as they were sure they knew the group. Also, I want the viewer to be reminded of the past, as our present is built upon those foundations, and also to remember that “our present” will soon be a distant memory as well. In that manner, we may become grounded and focus on what is truly important in life. Finally, in the way that I compose my paintings I hope the viewer will recall that we all see through different lenses.

We are curious about your background. When and where did you first get into painting? How did you manage the transition from being a critical care physician to a working artist?

“Evening Shift”, 2019

I have always been interested in art. As a child, I would draw. As a freshman in college, I did charcoal sketches of many of my friends, and dabbled in watercolor (not my media). My junior year of college, I discovered ceramics and it was an obsession. I was in the ceramic studio 5-6 days a week after finishing my pre-med studies. Fridays, mixing a few hundred pounds of clay or firing a kiln with friends, and a bottle of wine was a familiar scene. I considered changing my majors to Art that year but took the easy route and went to Med school. I continued to work with clay my final two years of college. I resumed clay around 1995 after completing my Internal Medicine residency and fellowship in Pulmonary and Critical care in 1989. I completed a graduate certificate in Ceramic Art at Hood College in Maryland in 2008. I was teaching some ceramics at the time and had a home studio. I had planned on continuing to create ceramic murals, sculptures, and pottery forever.

In July of 2012, I was diagnosed with Stage 1 multiple myeloma, a cancer of antibody-making cells. I took 8 months off from my medical practice for treatment. I returned to practice part-time in March of 2013 and found that I was unable to keep the pace because of side-effects of the treatment. I retired in June of 2013. I found that ceramics was too taxing to continue, and so I turned to painting. Initially, I just made marks on canvas paper; they were abstract, made without judgement. This was an important transition; I was fatigued, angry, and suffering from multiple losses simultaneously. I didn’t need judgement of any kind. Painting provided respite and connections, as I began to take some classes and workshops. The non-objective work ultimately gave way to realism, perhaps as a means of bringing order to what was at the time the chaos of my life. I returned to portraits with my first painting, a grey scale study of my wife in acrylic, and from there I moved on, seeking challenging subjects and images. In short, my transition was made for me, I could no longer practice medicine, or my ceramic art. Painting saved my life.

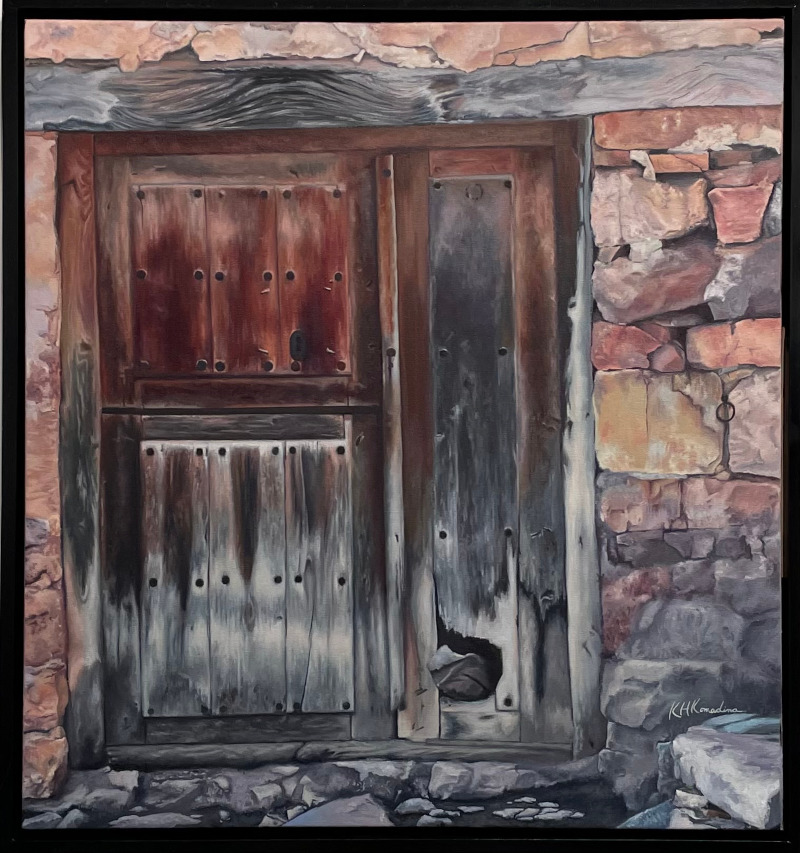

“O'Keefe's Front Door”, 2021

Your website summarizes your work as follows: “The fleeting images of everyday life, and the places where we live, work, and play, as well as the things

we create and leave behind form the body of my work.” – How do you turn abstract ideas of loss, space, and ephemerality into art?

While many of the paintings that I create represent static moments in life, “At the Museum”, “Evening Shift”, and “The Breakfast Club”, they collectively reflect the arc of life. Mother and child, working adults dining out, and retirees having coffee at McDonald’s illustrate different epochs of life, each with its own joys and challenges. Other paintings, such as the Vegas series, are each one a metaphor for life. It occurred to me that Las Vegas embodies all that is human: ambition, joy, sorrow, greed, corruption, desire, creativity, and beauty. The signs reflect the arc of their lives: birth, youthful vigor, success, and then retirement, sometimes to obscurity, and at other times memorialized. I found beauty in their imperfection, the wear and tear rendering them more interesting and perhaps reflecting their storied histories. “Glory Days” is an example, except for the Sahara, the other casinos represented in the painting have closed. The artifacts that remain are broken and damaged, bulbs missing, metal bent, and paint peeling. Liberace is long forgotten by many today. They all had their time in the sun, but fame is fleeting. However, despite their imperfections and age, they retain a unique beauty. For me, if I had idealized the images in “Glory Days”, eliminating the imperfections, it would be less impactful. Our injuries, our disappointments, our imperfections are all part of the whole that make us human and give us depth.

“Glory Days”, 2021

What do you appreciate about exhibiting in galleries and at art shows? Which challenges do you face when it comes to public exhibits?

I enjoy meeting with and interacting with people and learning things about them. For me, art is about communication and making connections, and that is what art shows and gallery openings allow. The biggest challenge of public exhibitions is the risk and vulnerability of putting one’s work on display. It is impossible to separate the art from the artist. Each work is imbued with who we are and our experiences. So, the challenge is to not personalize any particular reaction to one’s work as good or bad. I can only make the work that I am making at this moment in time, it may evolve, or not. Praise, if personalized, may result in the ego taking control, criticism, if personalized, may discourage experimentation. The challenge is to accept both praise and criticism as opinions, to learn something from both opinions, and to maintain artistic integrity. Trusting one’s inner voice I think is crucial. All of that of course is easier said than done.

Reflecting on your career of thirty+ years in the arts, which work are you most proud of to this day and why?

In 2010, I traveled to a small mountain village in Guatemala named Xepocol (pronounced: “Shay po cole”). The population of the village is about 1,600. The most common trade in the area was weaving beautiful textiles. I made three trips each of 2 weeks duration as part of a mission group that was involved with construction projects. My intention was to help them set up a small pottery in the village. We coordinated with the local pastor and the people of the church, and built a kick wheel on the first trip, we purchased dry clay in a nearby large city. I taught them hand building, and wheel work; on two subsequent trips we continued working with clay. On the second trip, we attempted to barrel-fire the work with disastrous results, and on the final trip, with the help of two young potters, we constructed a primitive wood burning kiln, and successfully fired the work that was created. In the end, six weeks in the country was not enough. The wood it took to fire the kiln was expensive, roughly $50 in the local economy, which was 2.5% of the average annual income of a person living in the mountains of Guatemala. There was local clay, but it was very coarse, useful for making tiles for a roof, but not as useful for pottery. Lastly, we made a simple glaze of wood ash and borax, but there was not a local supply of borax available. Traveling to obtain appropriate materials would have been prohibitively expensive for the people. To be successful would have required several months in the country, experimenting with the local resources.

So, on the face of it, the trip was not successful in establishing a pottery in the village; in truth, it was an abject failure in achieving my goal. However, as a result of the trip, I experienced the warmth and hospitality of the people. I learned that joy is possible living in adobe homes, without amenities, and the hard work of survival. I experienced an acceptance and a sense of community that feels rare to me. When I became ill in 2012, I received messages and prayers from the people of the village. I remain in contact with the pastor and a leader of the church, and the NGO director who coordinated the trip for our group. This experience probably explains my fondness for the painting “Los Abuelos”, a commission I did for a US friend from Guatemala whose Grandparents still live there. The painting reflects a warmth and tenderness of the couple, as well as the challenges of life that they faced.

You’ve worked with clay, created ceramics, pottery, and murals in the past – what have these art practices taught you that you can apply when creating oil paintings?

When I was creating ceramic art, I would describe the process as a dialogue between the clay and I, particularly when working with sculptures and murals. I would begin to build a piece and then step back and wait for what it would tell me it needed next. I would make a change and then assess the result. Not all change is good. This back and forth would occur until I was satisfied. With pottery, I would sketch various designs and then go to the wheel. The same process has developed with my paintings. I have a reference image as a starting point, from there I make adjustments and decisions, emphasizing this aspect, minimizing another, or completely eliminating something that doesn’t serve the composition, or making colors more pleasing, especially if working from a photo.

For certain works, and early on, I used a palette knife extensively. It felt like working with clay and was easier for me to control than the brush. With the palette knife, early on I could easily layer one color atop another wet on wet; with a brush early on I would end up blending the two. With my current work a brush is easier to accomplish my goals, though I remain agnostic about how to apply the paint to canvas. Whatever achieves the desired result, works for me.

“Los Abuelos”, 2020

Have you ever dreamt of a certain art piece or painting, and then brought it to life?

This happened once. I woke up early one morning dreaming/thinking of my mother’s violin, which has lived in a house with me since I was a child. I still have it. I never heard her play it, as she died when I was young. I had a vision of it along with a flower. The bridge of the violin is loose, one of the strings is loose, and the bow hairs are gone except for a few strands at the tip. I woke up and gathered materials, the violin, the bow, a Tibetan singing bowl, and a lily; it was spring, and we had an arrangement of them in the house. I set up the still life, did a rough oil sketch and then executed the painting over the next several days. “Lost Song” was the result.

“Lost Song”, 2018

Artists seek inspiration from many different sources. Can you reveal a unique source of inspiration for you and how it has helped to create your unique style?

I’m not sure that I have a unique source of inspiration. I am drawn to images that move me in some way, and that I feel others can connect with. The senior citizens in McDonalds, for example. Regardless of our age, race, sexual orientation, or politics, it felt like an image that most of us recognized and could feel some attachment to, or at least recognition. There are plenty of artists addressing the things that need to be corrected in our society, and that is important work about change that needs to happen and must happen. I hope to remind us of our common humanity.

“The Breakfast Club”, 2020

Can art help us heal? Elaborate.

Yes, I am a living example of that. When I retired in 2013, by necessity, not by choice, I was grieving, unhappy, and angry. While I knew that being a doctor was merely a part of my whole person, leaving a 50-60 hour/week-job leaves quite a hole. I had suffered the loss of career, status, income, physical energy, connections, and had to confront the fragility of life. My media of choice was no longer an option for me because of the energy and effort that clay work demands.

Painting gave me an outlet for expressing some of that. My initial non-objective paintings reflected those emotions and the chaos that I was experiencing.

As I enrolled in classes, and began to connect with the art community, that helped me with the loss, and reestablishing an identity.

To be honest, up until early 2018, I felt like I was going through the motions and not fully engaged. In 2018, I took a 12-week class with Joe Paquet,

a nationally known plein air painter. It was a winter studio class. Something happened in that class, and I woke up; perhaps it was his quote on the wall

from Rainer Maria Rilke about finding beauty in our immediate world, perhaps it was his enthusiasm for teaching, and his commitment to excellence. I’m not sure,

but something woke up in me early that year, and I remembered a favorite artwork at the Minneapolis Art Institute, and the joy that it brought me. That summer

I joined a studio group in Northeast Minneapolis and have been in the building working or as part of a gallery group ever since.

Yes, art heals, it gave me my life back.

“Dreams”, 2021

What are you currently working on? Can you give us an insight into future projects?

Right now, I just completed a commission portrait of a former colleague’s daughter killed in a hit and run last year. It was challenging on many levels. I’m also finishing up a fun painting in preparation for my road trip to “The Other Art Fair LA” at the end of September. When I return, I hope to have collected some interesting images from the road trip. I also have a series of portraits I have been meaning to do, one is of a potter friend trimming a pot on the wheel; her hands are a prominent feature. She uses a mirror when she works, and her hands lead the eye to the mirror where the expression on her face is one of pure joy. Also, a series of paintings featuring windows and doors is brewing. “O’Keeffe’s Front Door”, “Dreams” and “Castle Gate” seem to be the beginning of that series.

“Castle Gate”, 2021

|

|