Artist Interviews 2022

Toufik Medjamia

By Julia Siedenburg

Your art pieces are very versatile from photography to prints and sculptures, you can do it all. If you would need to choose one, what is your favorite art medium?

It’s a tough question because I really enjoy using different mediums. Each one has specific qualities. The idea you want to express actually dictates the medium. So I try to use the most efficient one to achieve my goal.

But I have to confess I always go back to drawing: it is where everything starts. I also thrive using different techniques and learning new skills while perfecting the one I use most. It’s a creative ecosystem where each practice nourishes the other and helps generate new ideas, sometimes making me go to places I didn’t expect. I hate routine, especially in the creative process.

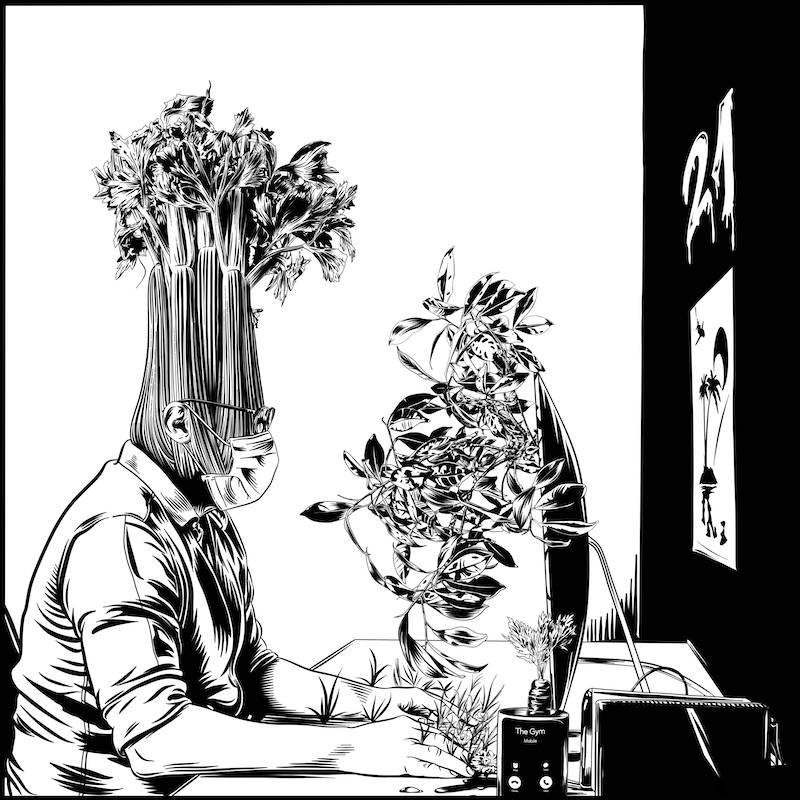

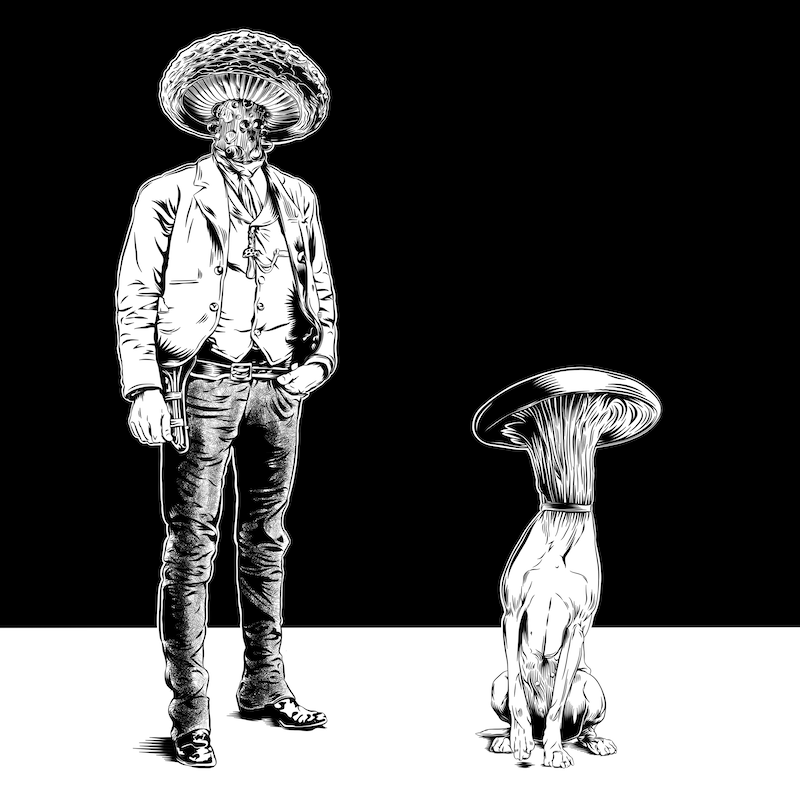

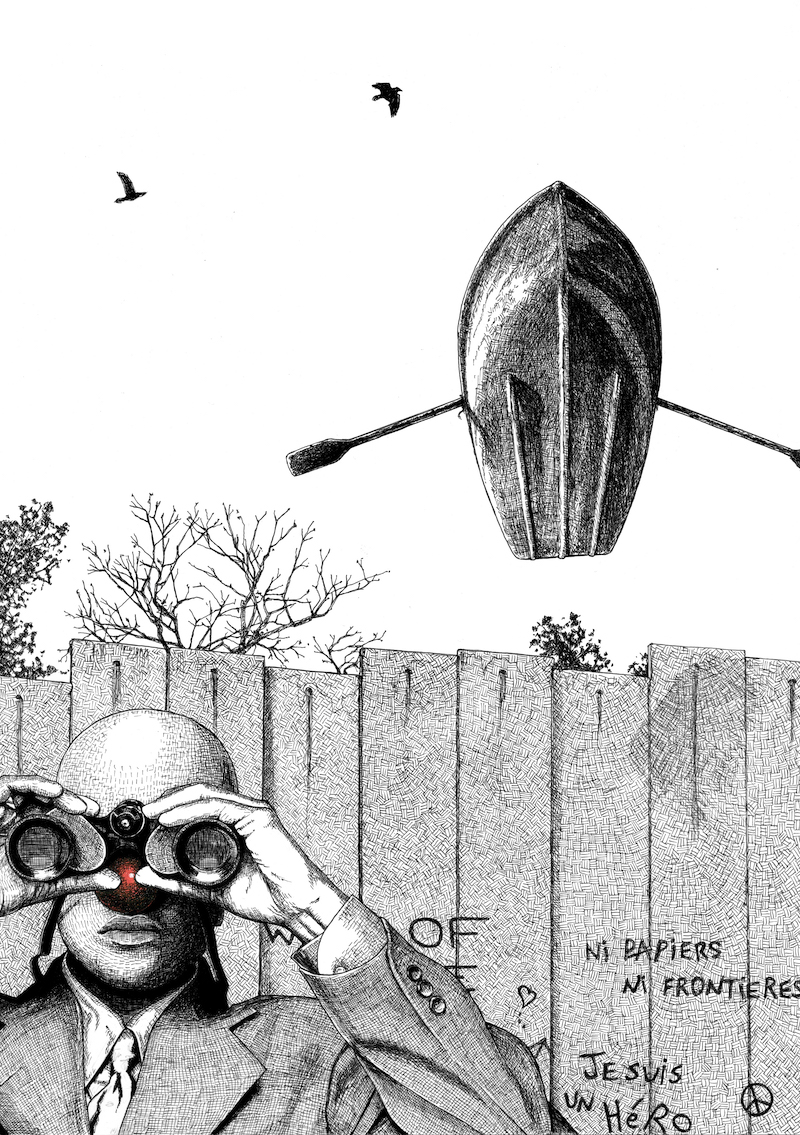

Your contemporary prints are a mix of partially realistic like a man sleeping on the couch in a packed apartment, a close-up look on a full sink, and then there are the fantastical pieces.

The fantastical ones showcase people with mushroom heads, pants drying on the moon, and a man with wings, to just name a few. How do these ideas come to you?

Reality itself is full of fantasy, we just need to break with the logical perception we have of it and try to see ordinary things in different layouts, shapes or proportions. What we call reality is mostly a common ground that helps us communicate and it’s only real because we agree about how we discern it. If you push it, there is no such thing as unbiased reality or even reality at all. I try to connect realistic things that don’t normally fit together in a playful way and see how it creates new meanings or emotions.

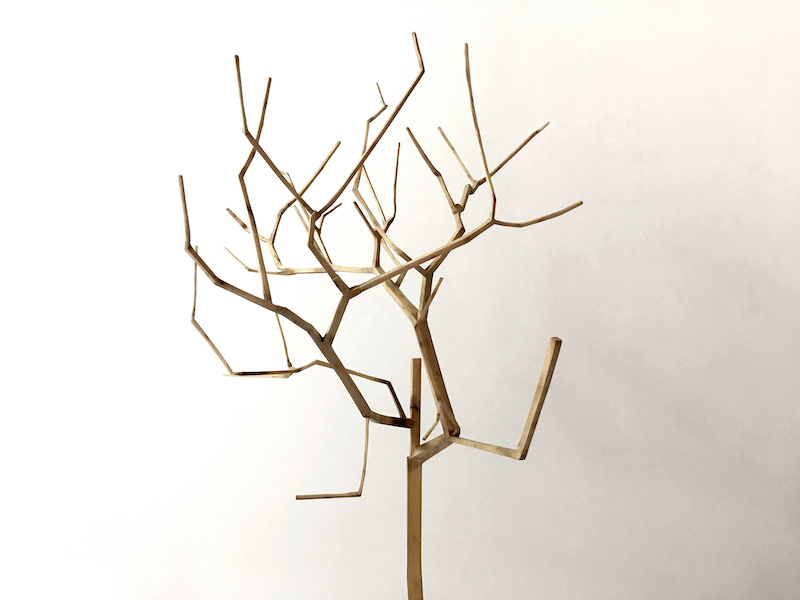

Tell us more about the process and inspiration of your wood carving sculptures.

The inspiration is the same as I described earlier. This series of sculptures started when I found a small dead olive tree by a dumpster. The tiny tree was beautiful and looked like a bonzaï. It was odd to see it discarded with the garbage. It’s the quintessence of urban behavior and relationship to nature. I mean, if I was living in the country side and had a dead plant, I would use it maybe as compost or would try to turn it into something useful or at least ornamental. I would not put it in a dumpster. It felt uncanny to just leave it there so I took it. I wanted to recycle this tree in an urban way. This was the main idea and this particular one became what I called a « rational tree » –making all the branches and trunk rectangular and ready to use for construction or structure set up. After that, I realized that there were a lot of people leaving dead trees in the streets of Marseille. I found plenty more, mostly olive trees. I brought them to my studio and carved them. It felt sort of like finding contemporary fossils. It’s where the idea of carving them as bones came. I was just like an archeologist peeling away the wood material to reveal the inside bones structure. Somehow, the result brings to light the original life form.

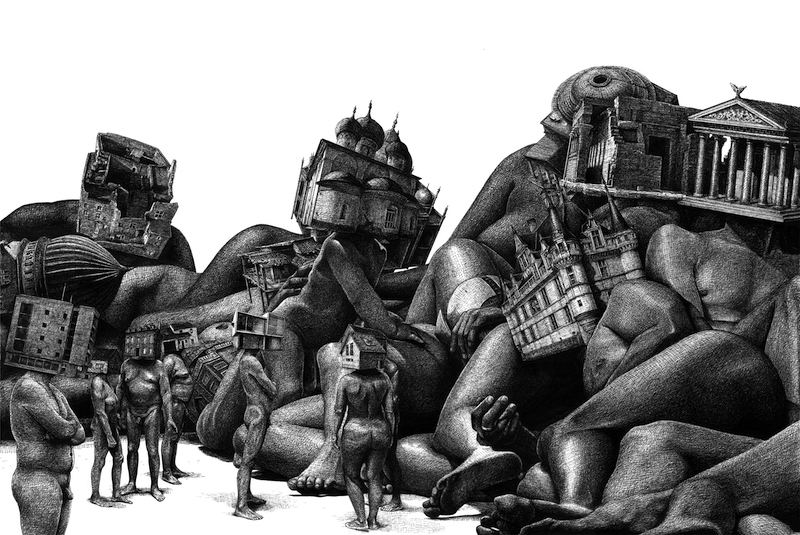

Some of your images can be seen as criticism of today's society and current conflicts. What is your main message to your viewers you are trying to convey?

My early works were more overtly political. Some of my main focuses where on colonial history, stereotypes and racism. And to be honest, it was painful on various levels. At that time, I needed to understand and study this complex history because of my background. Being North African, an immigrant and a young man meant I was often seen as a threat, someone whose « nature » made him suspicious. It’s clearly not how I defined myself but it was how the society I lived in saw me. Clichés take a toll on individuals and it seemed obvious to me that I needed to address this issue in my artwork. And I did, without any restraint. As I said, I was young. I learned a lot and it was really personal. I firmly believe that understanding how colonial history shapes the way we see each other and perceive our differences is a game changer. It’s a major issue and there is no perfect way to talk about it. The downside was that each time I had an exhibit the reactions where really violent. Art shows turned into political confrontations with people (mostly white people) who just didn’t get it. I mean, it wasn’t only that they weren’t affected by the issues, it was like I was showing them an alternate reality, something I had completely made up – because some people believe there is no such thing as discrimination, dehumanization or even colonial violence and war crimes. Just to contextualize, the dominant belief in France is what is called « universalism ». The idea is that you are French and nothing else. If you don’t comply, you are an « enemy of the Republic ». For example, racial statistics are forbidden so there is no raw data that can be used to study and highlight systemic discrimination. It’s the way here, all of that just « doesn’t exist ».–sexism, patriarchy, homophobia, LGBTQAI+ discriminations, nothing. We all are equal BUT each one in their « natural place ».

All this made me really question my way of addressing these issues. I might have been clumsy, might not have understood all the intellectual stakes that I was dealing with and so many other questions. Being able to reevaluate your work, your reasoning and even yourself is for me an important part of being an artist. Ultimately, the real question was "What is my place as an artist ? Do I need to convey a message and if so, what kind of message ? For what purpose ? »

To be honest, these are open questions and I have only temporary and contextual answers, depending on what I’m interested in at the time I’m doing it. But one thing became clear to me, freedom is an illusion, there’s no such thing as absolute freedom. Art is the only place where you can experience a glimpse of absolute freedom. I wish to convey some of this free spirit in my work and share it with the viewers. Once the work is seen, it’s no longer my interpretation or opinion that drives the viewers, it’s their own. I’m an artist, not a propagandist.

You have lived in Algeria, France, and the US. Are your motivation and inspiration dependent on your location? Which specific pieces were created in which city?

Yes, I was born in Algiers and grew up there. I moved to Marseille, France, when I was 16 and still live there. I have never lived in the U.S. but I have family ties in Chicago, so I go there often. I have had the opportunity to travel in a lot of different places, mostly Africa and Europe and Chicago is by far my favorite city.

It doesn’t really matter where I am to create but traveling definitely is inspiring. I like to be able to work anywhere I am, even if I have my routine in my studio. But being able to create wherever you are is thrilling. Often, I start a piece in a place and finish it in an other one. Sometimes, I have an idea while away and work on it when I’m back home. It gives me time to think about it and sharpen it. Traveling becomes a part of the creative process.

Though for the wood sculptures we mentioned earlier, that was really specific to Marseille: it’s not everywhere that people use tiny olive trees for decoration and throw them in the street! I also did my first cut out installation entitled « Superheroes never die ! » in the Moroccan city of Oujda. This work was specific to the location and the place. However, because I sketch and draw wherever I am, even these paper sculptures and cutouts where designed in different locations.

Your paintings are so detail oriented. How long does it take for you to finish one piece?

Well I am detail oriented, probably too much so. Depending on the work it can take several weeks and sometimes even months to complete it. I don’t really care about how much time it takes, working on a project long term makes me see the same work with fresher eyes and helps ideas evolve. I like it this way but it doesn’t happen all the time. Sometime the idea is set at the beginning and I have to admit it can be boring to just complete that work without surprises. I feel like a brainless machine processing a task. It’s why I usually work on multiple projects at the same time. Also, I can get lost in details so it’s hard for me to know when to stop. You can express what you seek in really few shapes or lines so why go crazy with details ? It can be a struggle sometimes to know when it’s enough. I am still trying to find the perfect balance between substance and shape. Details are not meant to be a skill demonstration or an attempt to reproduce literal reality. Machines can do that.

The image of director Spike Lee stands out immensely. Why did you decide to paint it?

Spike Lee was able to address sensitive topics in a subtle way, far from mainstream clichés. I think he paved the way worldwide for a lot of people to speak up in their work and not only in the movie industry. I admire his work for that reason as well as for the proactive way he does it. He does the right thing (pun intended)! My favorite movie is Bamboozled. For me it’s by far his best movie. There’s everything: it helps understand what racism, alienation, stereotypes are and how they are conveyed in mainstream culture with merchandising and TV and more.

Which of your work pieces is your favorite and why?

My favorite pieces are always the ones I’m working on and the future one I’m thinking of. Once I complete an art piece, I’m done with it. Letting go is necessary to move on. Each piece is a step to another one. It’s like climbing an infinite ladder: it’s best to look toward the top even if sometimes you look down to measure how much you have climbed.

What is next? Which direction will art take you?

Well, I truly don’t know precisely and I like it this way. I always seek new ways to tackle my work. It can be technical approaches using new tools and learning new skills or addressing new topics I’m interested in. It takes time to get in motion and I leave myself room to be surprised. I’m currently working on a comics project. I have always wanted to develop a long story. I also wish to publish a collection of drawings. These are more personal objects people can own and enjoy for themselves.

|

|