Artist Interviews 2024

April Werle

By Laura Siebold

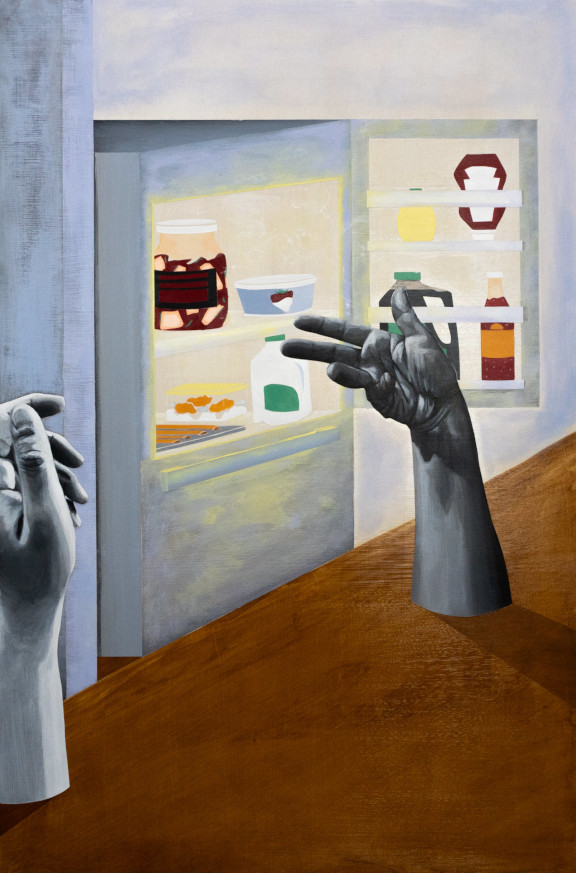

In April Werle’s paintings, she lets the hands speak. The 29-year-old American-Filipino painter who is based in Montana draws inspiration from her childhood and her mother’s strong hands.

April’s paintings tell a story of hope and resilience, of exploring one’s own identity between cultures and finding a sense of belonging. The narrative painter tells us about her growing up in

a mostly white community with some interracial encounters. April’s dedication in visualizing cultural diversity and transformation of cultural heritage within the Filipino-American community

is at the core of her work, and very much in support of this issue’s focus on art with a cause.

April, I love the meaningful use of hands as subjects in your work. What do the hands

signify and how did you come up with the idea of using hands as the central element in your

work?

I first started drawing hands as a kid. I remember being mesmerized by my mother’s working hands. I was struck by how elegant they were, but scarred and strong at the same time. I began drawing hands to give to my mother as little art gifts when I was growing up.

Fast forward to undergrad, I was using my body as a way to explore themes of mixed-race identity and belonging. I was in a drawing and performance class and used imagery of my body to focus on my skin. In a performance, I painted half of my body in white latex paint and spent the performance stressfully rubbing the paint off with my hands. In another piece, I took nude portraits and edited them with different black and white filters. In one version, my skin was as white as possible, and in the other version, all of my dark undertones were visible.

After I graduated, I began teaching myself how to paint and wanted to reduce the figure into what I felt was more universal than my portrait. That’s when I came back to hands.

You are Filipino and reside in Montana. In which ways does your heritage influence

your identity and feeling of belonging? Did you grow up in an artistic household?

I grew up in a small Filipino community in Montana. My parents had an arranged marriage that was put together by my auntie. She is about 25 years older than my mother and was already living in Montana with her husband. I feel incredibly lucky to have had a community of Filipino aunties and their mixed kids to grow up with.

My feeling of belonging has evolved throughout the years. As a kid growing up in a very homogeneous community, my mother instilled Filipino pride in us at a very young age. She would always tell us, “You are Filipino, and you should be proud of that.” She provided us with a shield that definitely came in handy. However, because I had learned to solely identify as Filipino, when I got older, I had an identity crisis when I visited my family in the Philippines at 15. There, I was first and foremost an American.

My studio has become a place where I experiment with balance. I’m learning how to be both Filipino and American at the same time. I’m also exploring in what ways culture was instilled in me and how I can expand and utilize those methods to share culture in my home with my partner.

As for whether or not I grew up in a creative household — my parents were always giving me art supplies as gifts. I spent a lot of time drawing portraits and furniture around the house, also coloring those black velvet coloring posters that seemed big in the early 2000s.

Your paintings form a tapestry of meaning. How do you explore mixed-race identity, belonging, and family in your work?

Currently in my studio, I am focusing on multicultural couples. I just finished a show called Secret Life of a Multicultural Couple that explores how culture is shared between two people.

I am really interested in exploring how the Filipino community is made up in rural places outside of large cultural hubs like LA and San Francisco. What stands out to me is that communities like the one in Montana look like this: immigrant Filipino woman, non-Filipino husband, mixed children. Of course, that is not every single couple, but that is the majority and that’s what I grew up surrounded by.

I’m interested in documenting how culture is passed or not passed down within the multicultural family, and why grandchildren are not identifying with the Filipino community. Our community is perpetually only two generations deep. I find this to be a great loss, so I’m taking the predicament into my studio to explore. How can stories help us talk about the stigma of multicultural couples, help us pass down culture to our younger generations, and how can we help our mixed-race kids find balance and a sense of belonging?

Do you have an artistic community in Montana that helps you grow? What are the challenges you had to face as an artist and as an individual growing up in a dominantly white culture?

I feel like I have two distinctive communities that help me grow as an individual and as an artist. I have one in Montana, where many of my artist friends are people of color. I am really inspired by the Indigenous art scene in Montana, as well as the many refugee artists we have here.

Primarily, the Filipino art community all over the diaspora has really helped me find my voice and has helped me grow tremendously.

It wasn’t until I started making friends and learning about other Filipino communities and their histories within the United States that I was able to see my own community from an outside view. Through this lens, I have been able to reflect on the specific challenges we have in rural places. It’s also helped me understand that hearing more stories of Filipino American experiences has introduced me to a diversity of experiences, creating more opportunity for connection.

The biggest challenge I have with being a person of color in a dominantly white culture is that I often feel very lonely. When I am around other people of color, especially mixed people, I feel like we have an unspoken understanding of each other's experiences — there’s a lot of validation and comfort in that. I would love to be able to walk out my door and feel that way most of the time. But I feel committed to staying and contributing to the Filipino community in Montana.

You call yourself “a narrative painter”. How do body language and storytelling unite and become alive in your art?

I call myself a narrative painter because I feel that the storytelling aspect of my work is the most important part. Before I started taking visual art more seriously,

I thought I was going to be a writer. I was a latchkey kid, and my babysitter was my notebook and pen. I would spend school summers on the trampoline,

in front of the TV, or in my room filling my pages with fantasy. My parents loved reading my stories, and I would always tell my mother that one day I would share her story.

I recently sent an image of a finished painting to my little sister, and she promptly texted me back to tell me, “It’s so cool seeing you do what you always said you were gonna do. You always said you were going to share mom’s story and now you’re doing it.”

I’ve learned that sharing my story is in part sharing my mother’s story, that they are intrinsically connected. And over time, I’ve learned that sharing stories that depict my family is sharing stories that deeply resonate with kids like me—stories of growing up in a multicultural family, in a predominantly white place, and who are grappling with cultural identity.

I use hand gestures as the driving narration in my work because I believe hands tell nuanced stories. I think there is a truth about a person that is revealed by their hands. My mother’s hands are tough, they are muscular. Her hands have scars collected from working her two to three jobs that she maintained my entire childhood and her love for cooking. She also has long elegant fingers that match her regal demeanor.

After using my full figure in my work for some time, I decided to reduce the figure. I felt that the human connection I was utilizing the figure for, I could achieve with just hands. My goal was to reduce the amount of context you could pull from the figure that would create subconscious biases from the viewer.

What has been the most meaningful experience you’ve had in your career as a painter? Was there a specific moment that assured you that you were going in the right direction artistically?

Sometimes, I will get really heartfelt messages expressing how my art practice has provided someone validation, especially when it comes to mixed-race identity from other Filipinos. These are the most meaningful experiences I have in my career as a painter because they, in turn, help me feel seen and validated.

Creating this work has brought me so much closer to my family, especially to my little sister whom I had a very strained relationship with growing up. Looking back on it, I held a lot of resentment for her because I felt like she got to be herself. As the oldest child of an immigrant, there was so much pressure for me to assimilate.

As I’ve used my practice to really reflect on my internalized racism, my upbringing, and how I want to contribute to my community, I’ve been able to dissect my relationship with my little sister, and I have so much appreciation for her and the person she has always been.

Since I started really homing in on cultural identity in my work, there have been so many moments with my little sister that have been magical and reaffirming.

Your paintings are dominated by earthy colors that feel grounding. In what ways has your style evolved during the past decade?

I started painting on wood during my last year of art school in 2016-17. I’ve always loved the way wood looks, and I’ve made sure to let the wood come through in all of my paintings.

In my early works I would mask in painted layers, creating abstract backgrounds with layers of house paint and collaged images of my body. The final piece would reveal exposed wood.

The visible wood in my work has often been related to skin. With this feedback, I started utilizing stains in my work. Now, I begin each painting with Pecan stain and Whitewash stain.

Do you feel that the current state of the art world has arrived at a sufficient level of cultural diversity, or is there still room for improvement? What are some projects or ideas you are working on to further strengthen the representation of Filipino culture in the U.S.?

As an emerging artist, I have found a lot of support from my local museums and arts centers, which even in Montana are making a push to raise PoC voices. These institutions have given me solo shows, grants, and have helped me grow to where I am now. As I grow outside of Montana though, I look forward to meeting more people who look like me in positions of power.

In 2024, my goal is to continue researching Filipino American history in Montana. Filipinos make up the largest Asian American demographic in the state, but most people wouldn’t know that. So often, we speculate the scale of an Asian demographic by their number of restaurants. There are only one to two Filipino restaurants statewide. Compared to other smaller Asian American groups in Montana, there is very little public representation, and virtually no recorded history of our presence and contributions here.

Secret Life of a Multicultural Couple is the beginning of my delve into investigating the history of the Filipino Montana community. Using my own experiences of navigating a multicultural relationship, reflecting on how my parents shared culture, and reflecting on how the Filipino women in our community share culture with their husbands and children, I’m exploring why our second generation perpetually leaves the community. I believe that our cultural identity struggles within our mixed-race second generation, contributing to why our presence seems invisible here.

Based on your experience, are cultural minorities being given the same access to art and resources as dominant cultures in the U.S.? How can art become a tool of self-expression for minorities?

Based on my experience, cultural minority artists often get stuck in the “community arts” realm because as we cross into the institutional realm there aren’t as many of us to advocate for our stories.

As I am researching more museums, collections, and galleries, I find that there are few that focus on artwork from the Asian diaspora and even fewer that focus on Filipino American artists.

In the institutions I have found, I have also noticed that most of the artwork captures the immigrant perspective. Although I find this wonderful and important, I would love to see more stories that talk about what happens with the children and grandchildren of these immigrants.

I believe art is a powerful tool to record and explore histories of minorities. I also believe having more Filipino American artists in major collections would greatly aid in recognizing our lived experiences and continued contributions to this country.

What is the legacy you would like to create with your art?

Growing up, I remember having to describe what a Filipino is almost every time I met someone new. I wondered how I could know so many Filipinos, and yet it seemed like no one knew we were even here. I found this so disheartening, watching my mother and so many of the Filipino women I know who work in healthcare, contribute tirelessly to the greater community—and yet the Filipino community was seemingly invisible.

I think this has bothered me so much from a young age that I’ve been determined to be visible.

With my practice, I want to make stories like my family’s and my community’s more visible. I want to shed more light on mixed-race experiences. Sharing these stories is how we strengthen belonging, which is crucial for maintaining connection to community across generations.

I firmly believe that maintaining connection to community is an opportunity to enrich our understanding of ourselves. There is so much we gain from understanding our cultural history. How do we build upon the progress of our parents, our grandparents, our great-grandparents, or confront generational trauma without understanding the people that came before us?

|

|