Artist Interviews 2022

Duncan Sherwood-Forbes

By Laura Siebold

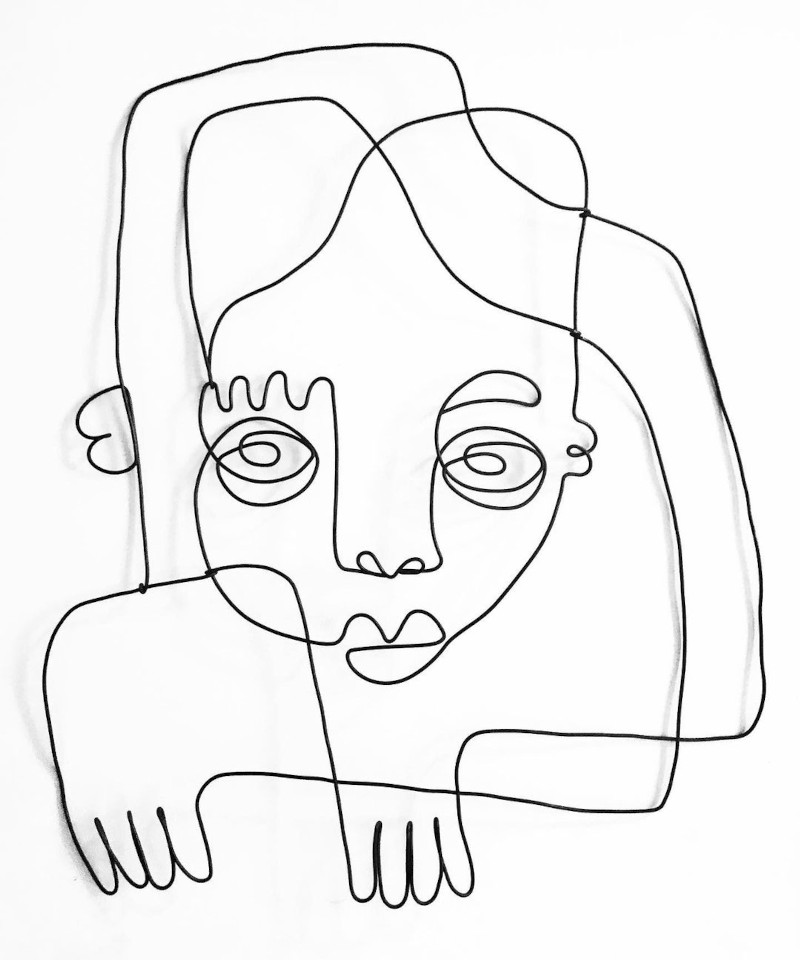

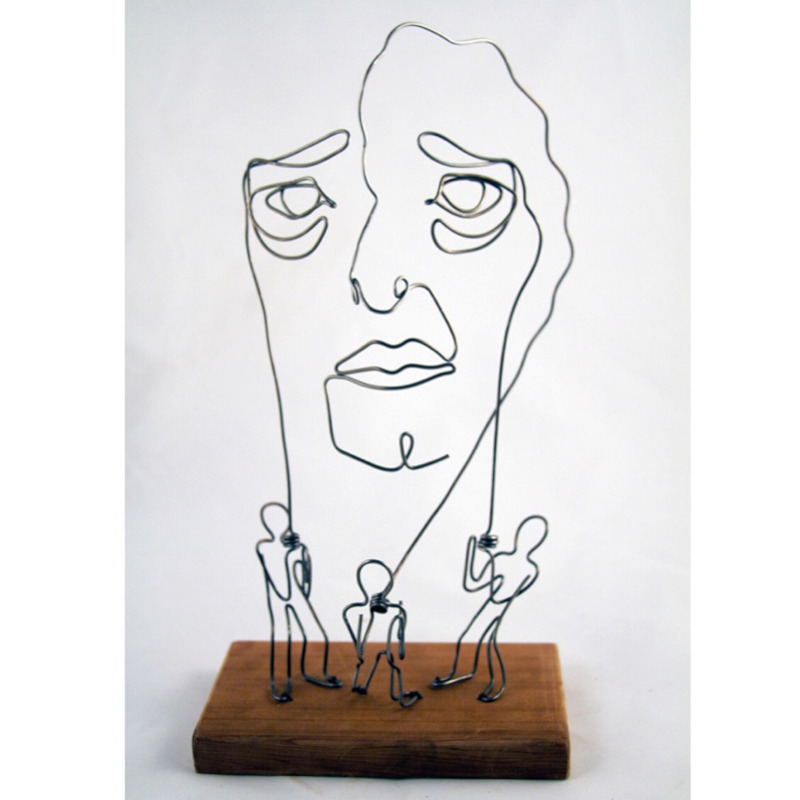

Duncan Sherwood-Forbes is as special as his name sounds. The artist’s focus on linear metal sculptures, animated by the use of sinuous curving line is at the forefront of his Los Angeles-based studio Wired Sculpture Studios. Duncan’s fascination with art began in his early childhood and teenage years, when he first started learning different skills and making a name for himself by exhibiting his work in galleries. Duncan is an artist who follows through with his unique style and does not limit himself to the guidelines of art school faculties, leading him to withdraw from his sculpture classes before finishing his degree in 2013. Duncan’s personal involvement with the recovery industry as a reand simultaneous work on his art and design practice led him to Los Angeles. Duncan continues to work in Wired Sculpture Studios and improves his fine art practice.

In his interview, the artist tells us the story behind his “Art Crimes” series, shares some poems, as well as some insights into his background and style, and reveals some tips for newly emerging artists.

Duncan, we spotted your art at The Other Art Fair in Los Angeles, CA. Can you tell our

readers a little about the background of your “Art Crimes” series? Was The Other Art

Fair your first exhibit after your works had been seized by the police?

Hello Laura!

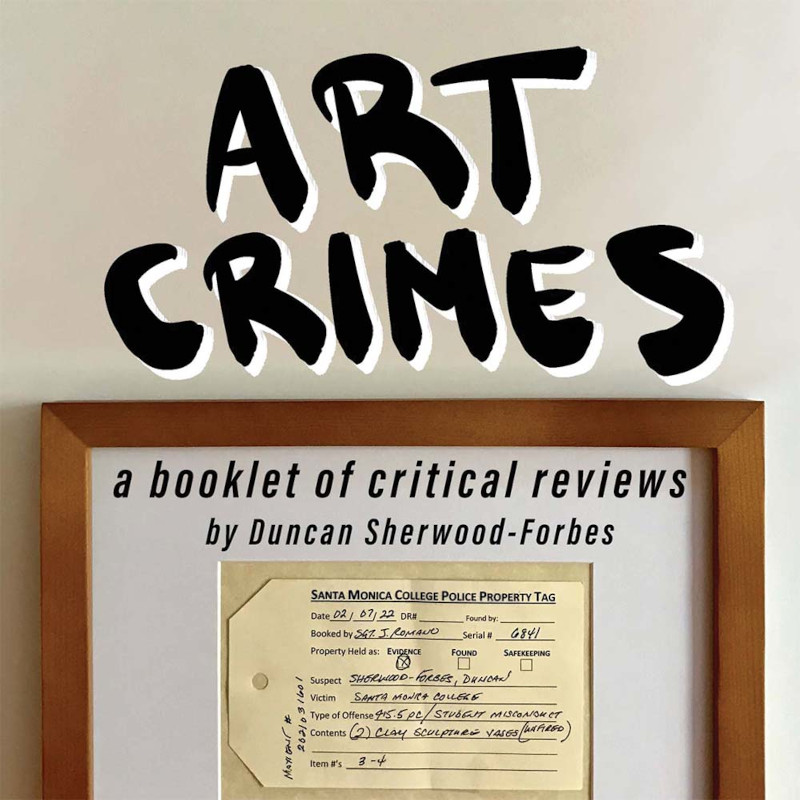

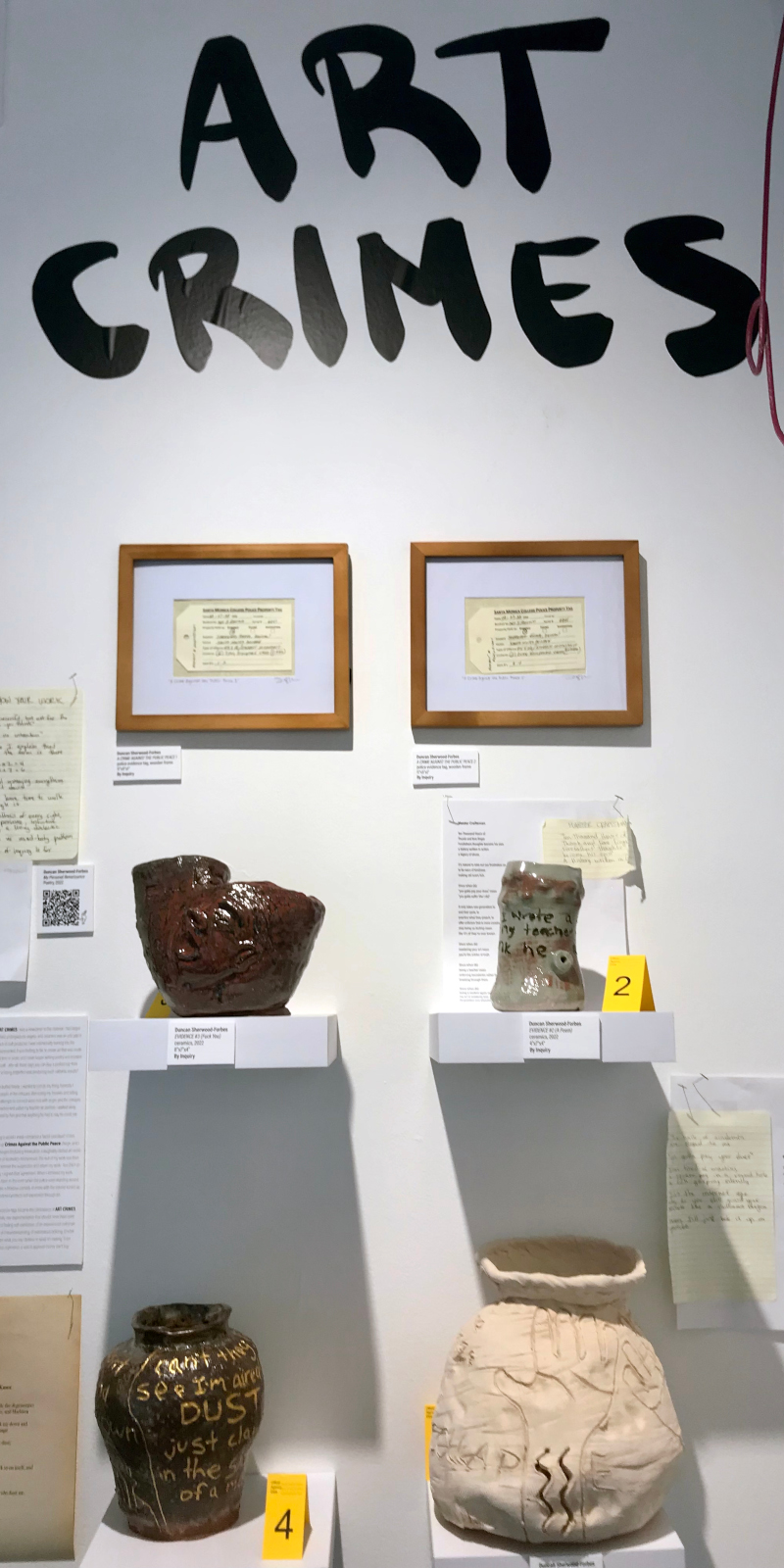

ART CRIMES is both a series as well as an individual multimedia work comprised of ceramics, police evidence tags, poetry, writing, supporting documents, and a booklet of select layman’s reviews of the work. Each individual work comes together to create the whole, a record of struggle, rebellion, overzealous policing, and transmutation. At its center are the four text-based ceramics works that the school seized as evidence of a Crime Against the Public Peace, along with the two evidence tags that came attached to them when I finally got my work back.

The ceramics work is far from perfect. I had begun casually taking classes at the local community college during the pandemic in pursuit of my unfinished undergraduate degree, something I had abandoned in 2013 due to trauma and nascent alcoholism. Ceramics was a gap in my artistic knowledge, so I decided to rectify the issue while simultaneously earning college credit on the cheap.

Being a novice was fantastic, I loved the human errors my lack of craft produced. I intentionally leaned into the imperfection, enjoying my mistakes and the record of learning they represented. It was thrilling to fail, to create art that was crude and offensive to my perfectionist side. I felt raw and free for the first time in years, and I even began writing poetry and incorporating it into my work. I constantly questioned the value of perfecting craft - after all, these days you can buy a perfect cup from IKEA for $3. Why would I waste my time perfecting craft when the act of being imperfect was producing such cathartic results?

Sadly, this attitude did not go over well with my ceramics teacher. We butted heads often, after all I was not the typical community college student given that I have many years of professional art experience. I would share my ideas with him, only to be shut down – he told me I wasn’t allowed to talk at that level without a degree and that “[he] has the MFA and [I] don't have shit." He even acted outside of his purview by telling me my wire sculpture is tame and I should stop selling it – and when I countered by telling him my wire work pays the rent, he became even angrier.

As the semester progressed, we butted heads more frequently, but luckily, I’m good at transmuting trauma into art. After each dressing down, I would create. I wrote a poem about the situation, ‘Master Craftsman’, and showed him the first few lines – which were complimentary, but it still made him angry. It was my theory that such a jerk could only be the result of being abused himself during his studies, a sort of five monkeys experiment of generational art school abuse. Another poem that arose from the situation I entitled ‘Entartete Kunst’, which called out art school on its fascist tendencies – a poem part of which I carved into my ceramic piece of the same name.

Master Craftsman

Ten Thousand Hours of

Thumb and fore-finger

forefathers thoughts become his own

a history written in action

a legacy of abuse.

it’s natural to take out our frustration on one another,

to be wary of kindness

making old scars itch.

Since when did

“you gotta pay your dues” mean

“you gotta suffer like I did”

It only takes one generation to

end that cycle, to

practice what they preach, to

offer criticism that is more constructive than combustive, to

stop being so fucking mean

like it’s all they’ve ever known

Since when did

mastering your art mean

you’re the arbiter of truth

Since when did

being a teacher mean

enforcing boundaries rather than

breaking through them

Since when did

being a student again mean

my art is suddenly less

De gustibus non disputandum est

Entartete Kunst

It would be my honor

To be presented alongside the degenerates

the Incompetents, Cheats, and Madmen

My teachers want to break my down and

reform me in their own image

Can’t they see I’m already dust;

just clay

in the shape of a man.

A tangled rope, turned back in on itself

fraying, and

bound with salt and tar

why am I so drawn to those who hurt me.

While calling out my teacher to his face could get me in trouble, the first amendment protects artistic expression, and I used that protection to bring all of my frustration and anger into the world. Eventually his verbal assaults got so frustrating I finally called Desmond an asshole to his face, walked away and later wrote him an email saying I'm no longer comfortable being cornered by him and that anything he had to say, he could say via email

I was definitely poking the bear.

His reaction was to report me to campus police on a number of fabricated charges, claiming I was drunk in class and that one of the vessels I made contained a "racist caricature" of him – despite him knowing that the piece was based on my own trauma and that the figure was an allusion to St. Maud. The accusation of intoxication was especially insulting, given that I’ve been a sober member of alcoholics anonymous since 2015.

Four of my text-based ceramic vessels were then confiscated by campus police on charge of Crimes Against the Public Peace, and I was suspended for a year. The school informed me that they would happily remove the suspension and return my work - but ONLY on the condition that I "voluntarily" withdraw from the school.

Begrudgingly I signed their agreement. When I retrieved my work, the four text-based vessels came with the EVIDENCE TAGS!

Oh, how I wish I could have been in the room when the police were standing around my work, asking themselves, “is this illegal?” It's an Orwellian nightmare, a Kafkaesque comedy of errors with the volume turned up to 11. I was never officially charged with the crime - after all the first amendment protects self-expression through art, something the SMC campus police clearly did not know.

Not one to be defeated, I turned those lemons into lemonade. Having already been accepted into Saatchi’s The Other Art Fair, I decided to take a risk and present the whole scenario as “art as a crime scene”. The evidence tags, my own personal ready-mades, were the centerpiece. And the ceramics works themselves, initially raw experimentation that should never have seen the light of day, now had real content. They were more than just the record of flailing self-expression by an experienced craftsman leaning into his amateur side in a new medium. Now they were a record of professional jealousy, of overzealous policing, and of what happens when a student challenges academia. Even though I had to abandon my studies to get my work back, their confiscation represents a seal of approval money can’t buy.

When did you first start creating your ceramics and linear metal sculptures? Can you

explain the concept of the sinuous curving line you use for your metal sculptures?

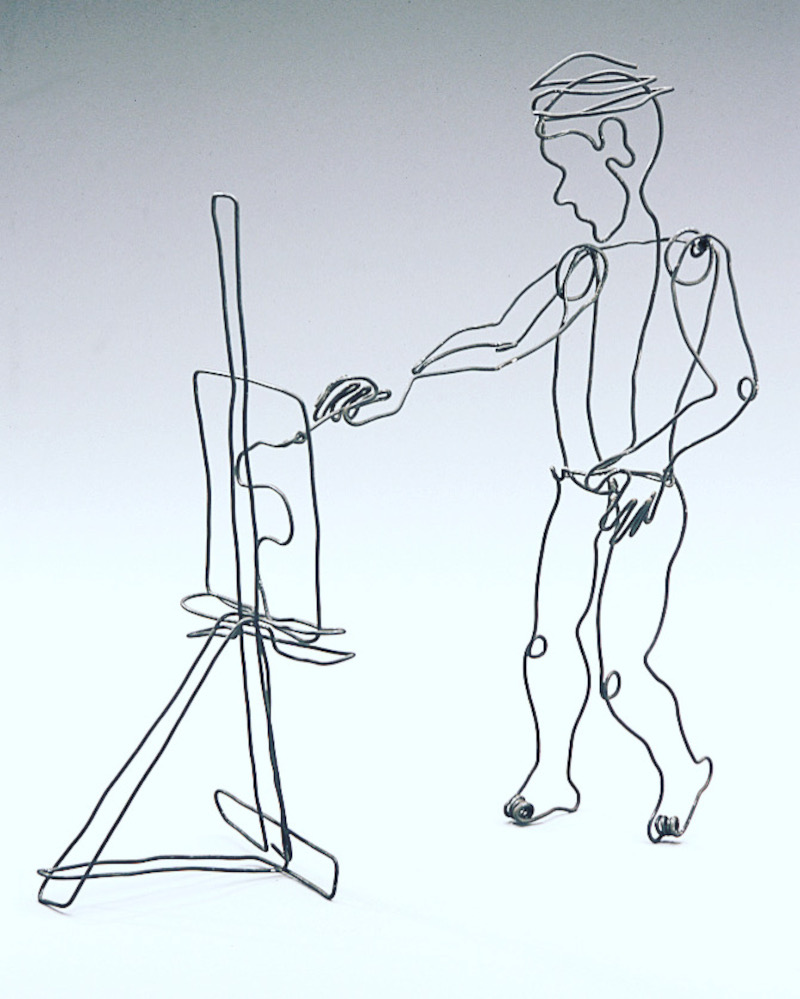

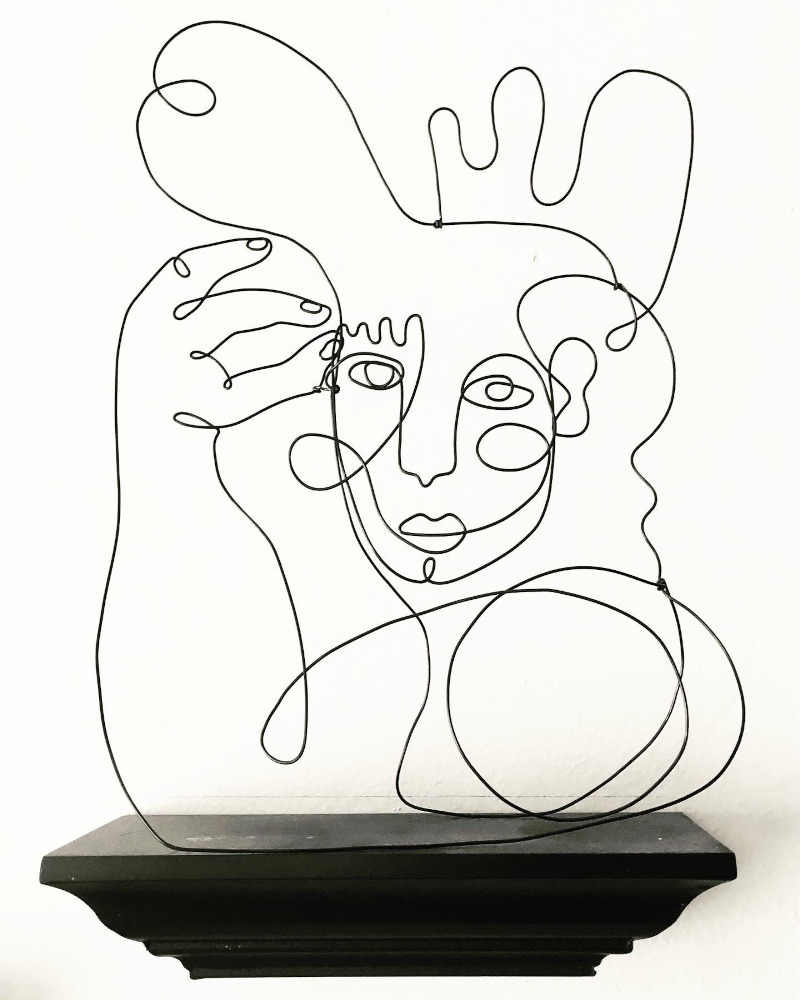

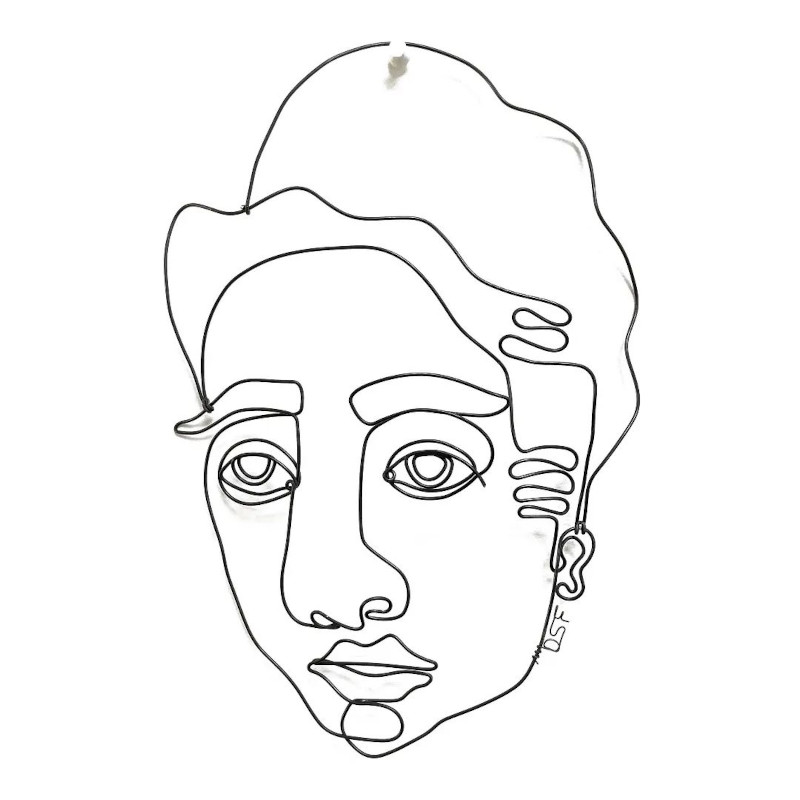

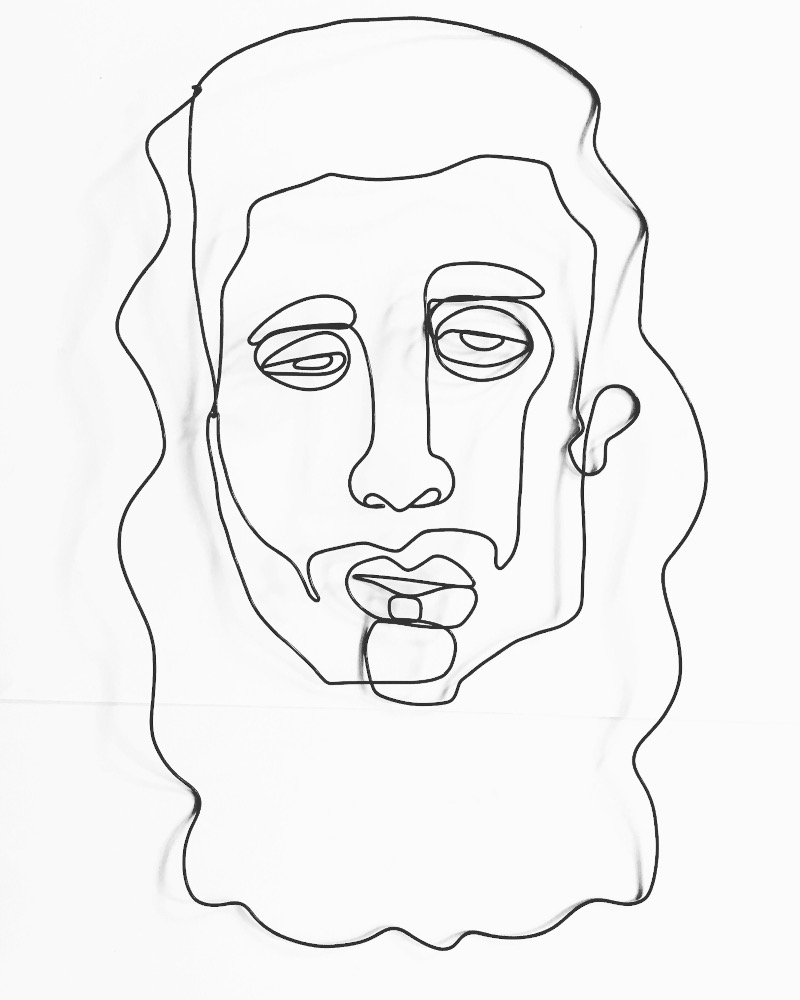

While I’ve only been creating ceramics since January, I have been creating linear metal sculptures since I was 16 – both wire sculpture and larger welded work. Over time wire has become less sculptural, and more of a way for me to draw in space. Wire allows me to bring line to life, and to draw in three dimensions in ways a pencil never could.

Can you tell us a little more about your artistic background? What made you decide for

the profession of the wire sculptor?

As a child I was an obsessive drawer, I mean obsessed. My father once got a giant roll of newsprint from a local printer, and I turned it into an epic scroll of Middle Ages warfare and dragons. I was lucky enough to grow up near the DeCordova Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts, which gave me access to art from an early age, as well as after school drawing classes. I was very fortunate to have parents who encouraged and supported me in my art.

In high school, I attended the Putney School for the Arts summer program, and at age 16 an instructor introduced me to wire sculpture. I immediately fell in love with the ability of wire to draw in space, and at age 17 I began selling my work at little art+flea markets around Boston and on Martha’s Vineyard. There was a famous wire sculptor who worked on the island, and I went to visit him at a market one time and to my surprise he had heard of me! I introduced myself, and he said “yeah you do the portraits, right?” with a bit of anger in his voice. It was not what I expected, and it was a thrill to be recognized as a competitor by someone who I thought of as a master of their craft. That and early financial success were huge motivators – at 17 I had my first juried two person show, by age 18 I was selling small work for $400+, and at 19 I got my first four figure welded commission (of 12 pets, however I no longer do pet portraits). That gave me the confidence I needed – and still need – to pursue art as a career.

What is your favorite material to work with? What is it that fascinates you about metal as

a material?

While I’m currently pursuing my love affair with ceramics, steel was my first love and continues to captivate me. Wire is a natural medium for some reason, for many of my portraits I work directly in wire instead of sketching it out first – in fact I prefer wire to drawing. And welding is an experience like no other – you learn to listen to the material, to know what amount of heat you need to bend but not burn the steel. Welding is very meditative, when I get in the zone, hours will fly by and I will work work work until I finish my piece.

Your metal sculptures leave room for the viewer’s imagination to complete the image.

How would you like your viewers to approach your art and what is the intention behind

your works?

I’m so glad you understood this!! There’s a fantastic theorist, Scott McCloud, who writes about comics. In his seminal work Understanding Comics he breaks down a concept he calls Amplification through Simplification, wherein economy of line allows the viewer to better relate with what they’re seeing. Comic protagonists tend to be simply drawn; however, the bad guys are complex – this is a purposeful move by comic artists to encourage viewers to identify with the protagonists and not the bad guys.

I touch on this in my work, I strive to find the sweet spot of providing just enough information to bring the viewer in. By involving the viewer in my work, I create a more engaging experience, which I think has led me to be successful in the medium.

You address important themes of trauma, identity, loss, and recovery with your art,

based on your personal history. How would you characterize your style? Where do you

position yourself as an artist and has your approach to art changed throughout your

career?

My style has changed a lot over the years – when I was in my teens and early 20s, I focused on people doing activities. It was fun and it sold well and provided great opportunities for aesthetic investigation. However, it wasn’t truly expressing my soul.

I actually gave up on wire – and art entirely - briefly in 2015 when I got sober. Drug use and artistic expression had become too intertwined, and I went into healthcare to help other addicts and alcoholics. In 2016, I found myself bending again, the urge to create was too strong. I found myself creating portraits of clients, and the addicts and unhoused in my neighborhood in a series I later called Angelinos, and it felt far more meaningful than “guy walking a dog”, ya know? It revitalized my love for art and my love for the medium of wire.

Today I have a Janusian approach to my practice – on the one hand I have my more design work and figurative wire work, which is certain to pay the bills, and I have my wild multimedia self-expression which is exciting and invigorating but rarely results in work I’m comfortable putting up for sale. The art world can be savage sometimes, and I’ve had people use my status as a recovered alcoholic against me (as seen most recently in the false accusations that contributed to my college suspension). But to enjoy art making, I have to do it with my whole soul. When I get pigeonholed into being a “wire guy”, I can get antsy, and I have to go outside of my normal medium to ensure my love for art stays bright. Often, I won’t know what I’m working towards, which is exciting, and after going wild for a while, I’ll settle down and bring new discoveries back into my wire practice.

Please describe one of your favorite interactions with viewers. How did this experience

change you?

I love when kids see my work; often their eyes light up and they run over and touch my pieces. They’re also fascinated by watching me work, I recently ran a specialty workshop at a camp in mid-city L.A. which was a smashing success. Kids are unburdened by art education and being told what to like, so seeing the genuine joy my work elicits from others just fills me with joy too!

Can you name an influential personality in the art field who inspires you to this day?

What kind of inspiration do you draw from this person for your own art?

Amy Sillman, Amy Sillman, Amy Sillman. She’s a fantastic painter, and I had the privilege of spending countless hours with her work back when I was a docent at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston. She had this show, One Lump or Two, and I spent hours in it staring at her paintings while on duty. She would do automatic drawing, being impulsive on the canvas, and then would step back and ask herself “what is this?” She would then start to make the abstract shapes more recognizable, but then would interrupt her process and turn the canvas 90, 180°, and then repeat the process. Toeing the line between abstraction and figuration, between play and work, is something I’ve taken to heart. Over 10 years later I think about that show often.

What has been your favorite project to this day and why?

Oh man, I’ve had so many fun projects. Portraiture is always my favorite type of commission, it’s a challenge to refine and reduce a face to the essential lines. Once I identify the key aspects of a person – it might be the eyes, the slight tilt of the corner of a lip, the eyebrows, I refine until I get it just right. And once I nail that aspect, the rest of the person can be a gestural mess and the client will look at it and say, “wow that’s me how did you do that!”

The project that gave me the most pleasure recently was ART CRIMES. There’s nothing more fulfilling than life giving me lemons and turning it into lemonade.

What has been your favorite opportunity to exhibit your art? What kind of advice do you

have for a newly emerging artist?

In-person art fairs! Working with galleries is great, but they act as intermediary between myself and collectors. With art fairs, I’m able to create and nurture relationships with my collectors, and I love knowing where my work ends up – when my work sells through galleries, I just get a check at the end of the month. It’s far less personal.

My advice for a newly emerging artist (although I’m still emerging myself) is to emulate the business practices of artists you respect. How did they start out? Where did they first show?

Second piece of advice is to operate outside of the establishment and embrace new technology and nontraditional mediums. Create your own definition of success and pursue it.

|

|